Forgoing race, embracing culture

Acknowledging the importance of culture in a racialized society

May 19, 2021

Surrounded by faces just like mine, I found a tight knit group of people connected through Korean culture, language, tradition, and heritage at Seattle Community, one of the largest Korean churches in Washington. Across the U.S., Asian Americans often struggle with finding a place to call home, so places such as Seattle Community provide a space of familiarity and cultural acceptance.

At first, I thought that these were my people because I belonged to this certain race of people, but the more I searched for community there, the more I realized I did not have it.

It’s more realistic to say that I’m American, not Korean. Although I still partake in certain cultural traditions, it’s only a small part of who I am. The language I speak, the media I consume and the lifestyle I live makes me inherently American. Quite mistakenly, I thought I’d find identity through my perceived race. I realize now that race is not about how I see myself, it’s about how others see me.

In the United States, there is an instinct to racialize people, politics, and religion without much consideration beyond skin color. Not to be confused with ethnicity, race is grouping together based on physical and social traits; it’s a concept.

It was only during the 16th century that the term “race” first entered the English language. From the age of exploration to the colonization of America, race was first used to generalize observable characteristics for people of different nations, mostly for the purpose of discrimination.

Stereotypical labels of black and white have lost their significance over the course of history because of their sweeping assumptions, but even the contemporary U.S. model of race is showing signs of guesswork.

Hypodescent is the automatic assignment of the children of parents from different groups into the subordinate group. Historically, this persisted as a way to segregate mixed race children as simply Black during the Jim Crow era, but still today the convention persists to imply that someone of mixed race is Black when genealogically, they are just as warranted to be seen as “White”.

It was only in the 2000 U.S. census that “mixed race” was finally added. This was a huge progressive step for acknowledging racial identity, but the term ‘mixed race’ is still ambiguous for identifying any specific ‘race’. Without proper terminology other than slang, vagueness in racial categorization runs the risk of possible hypodescent.

I’m not trying to say that race isn’t important or that colorblindness is a good thing.

Understanding how people perceive race is crucial for dismantling racism and white supremacy on an institutional and cultural level. Even for the global pandemic, it is necessary to discuss how the U.S. healthcare system has failed racial minorities so that equitable vaccine distribution and building trust is possible. Nonetheless, race is still a concept and although it’s okay to appropriately generalize circumstance, not everyone lives by it.

Compared to the race we see, culture is the richness of how different people live, think, speak, and dance. Compare someone from Seattle to someone in New York. Their life circumstances end up placing them in two entirely different worlds, not because of complexion or heritage, but because of culture. While race often implies sectionality and division, culture is a much deeper mesh of differences that inclines people to share and learn. It’s why people travel and explore, to experience different lifestyles, cuisines, and languages.

By the year 2045, 50% of the United States population is expected to be “majority-minority,” and with the rise of racial diversity, multiculturalism will expand and develop along with it. I believe that blurring our current definition of race will help people recognize that there is more than meets the eye.

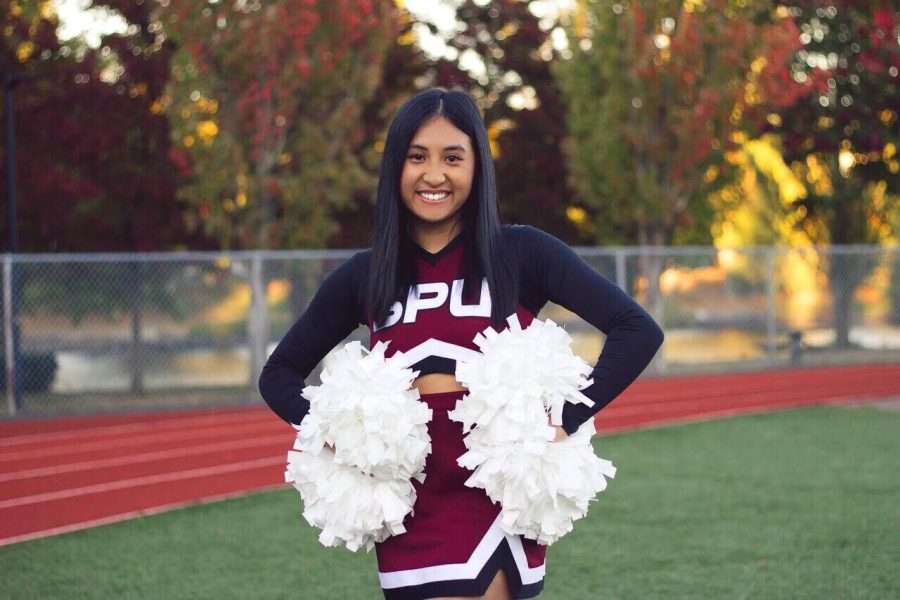

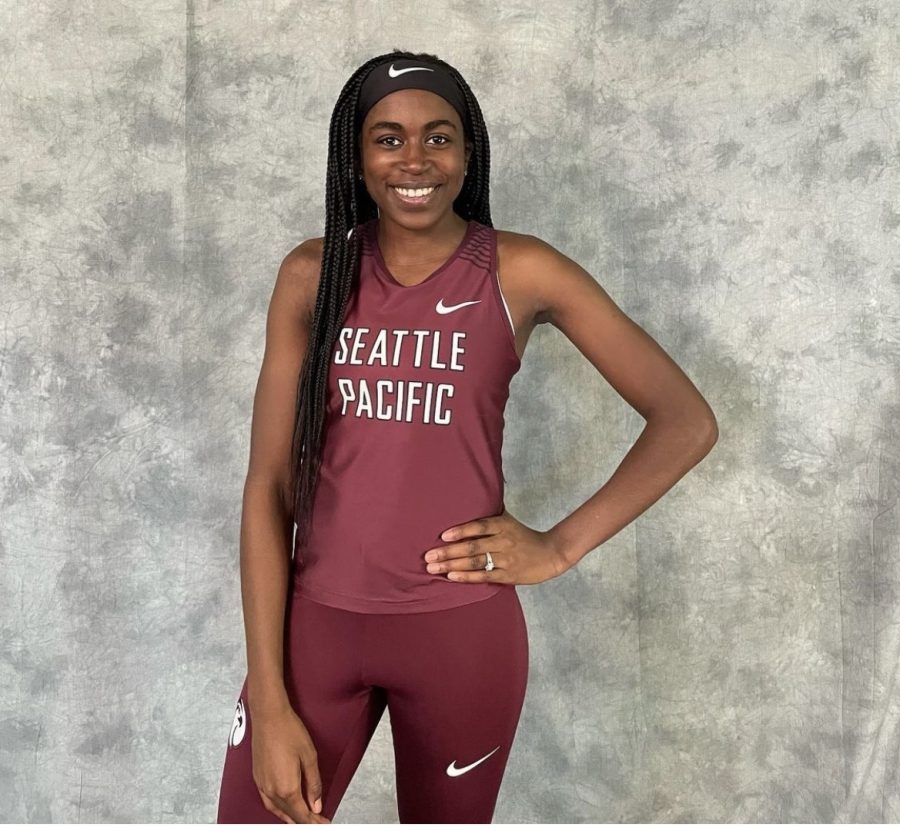

With my first year at SPU coming to a close, friends who have become “my people” share almost no resemblance to what I look like or where I come from. But through differences, we’ve created a culture of our own. I still love being American and I love being Korean, but that’s probably because I love being me.

Race is not how I see myself, but it is how others see me.

![Queer joy at SPU’s [Redacted] Fest](https://thefalcon.seapacmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/04_14_23_9999_1-600x400.jpg)