Cost of concentration

Stigma around ADHD creates unnecessary barriers

January 27, 2022

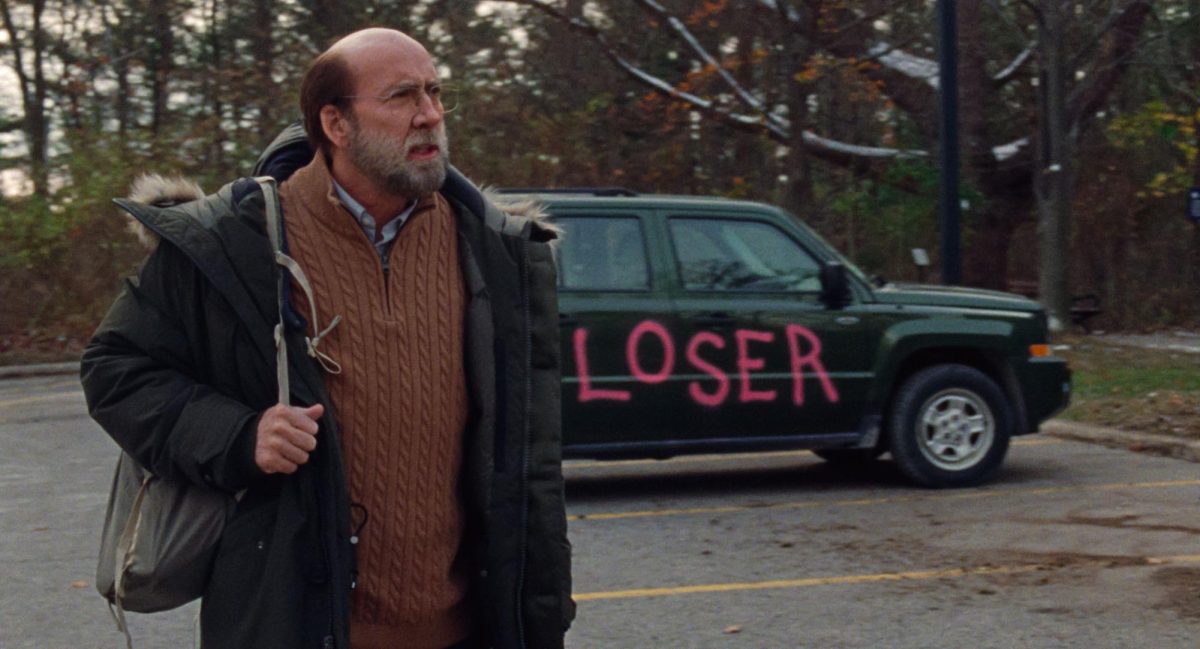

Last winter quarter, I failed every single class.

These days, this surprises most of the people I know, and they assume I’m joking. While I laugh it off now, the reality was quite difficult to experience. I started 2021 off with a grueling eight-hour virtual psych evaluation, scheduled conveniently on my 19th birthday. This evaluation was a necessity for me to receive medicine and educational accommodations to treat my ADHD, a disorder I had been struggling to manage throughout high school and the beginning of college.

In high school, despite my earnest pleading and the recommendations of multiple therapists, my psychiatrist refused to officially diagnose or treat my condition appropriately because I seemed to manage my responsibilities fairly well. The truth is, I dealt with intense mood swings, brain fog, intrusive thoughts, a lack of social awareness, a chronic lack of motivation and ability to focus and memory loss and dysthymia daily. I continued to uphold a facade of success through the extensive grace of my teachers and by self-medicating excessively with cannabis.

Upon research, this seems to be a frequent ADHD experience. In their research article Under Diagnosis of Adult ADHD: Cultural Influences and Societal Burden, Philip Asherson et al. state that “Some adults with ADHD may appear to function well, however they may expend excessive amounts of energy to overcome impairments; and they may be distressed by ongoing symptoms such as restlessness, mood instability, and low self esteem.”

So finally after my evaluation last January (scheduled three months in advance, for the earliest possible time), I was diagnosed sufficiently to receive the help I so desperately needed and I thought my struggles with ADHD were over. Unfortunately, they were just beginning.

Doctors have historically treated ADHD with a class of drugs known as ‘stimulants,’ and have an excellent success rate doing so. However, stimulants are registered as a Schedule II Controlled Substance, which, according to dea.gov, includes medicines described as “Drugs with a high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependency. These drugs are also considered dangerous.” As a result, my primary care doctor wanted to try some stimulant alternatives before prescribing a possibly addictive drug.

I trusted my doctor’s judgment and began a course of Wellbutrin (typically used as an antidepressant and anti-smoking aid) in February. Two weeks of intense-depression-with-violent-intrusive-thoughts later, with my late assignments piling up, I called my doctor and switched to Atomoxetine. After a few weeks, my blood pressure was dropping every time I stood up and my head was even foggier than before. I still couldn’t do my chemistry homework without tears. My doctor decided to try me on a course of Methylphenidate.

After a couple more weeks, I was inescapably behind in every class, and my ADHD symptoms hadn’t improved. My doctor reluctantly prescribed a short round of Adderall and told me I would know within the day if it worked for me. I sat down and worked on my overdue chemistry homework for five hours, each problem I solved bringing me more joy than the last. I excitedly messaged my doctor that it had worked, that I was so happy and that I was able to do basic math in my head again for the first time in years. She wanted me to finish the short course before prescribing any more.

A couple days into spring quarter, my prescription ran out and my doctor wanted me to try another half-filled prescription of Adderall to make sure it was the appropriate drug before fully prescribing it to me. After that round of Adderall, she decided to shift my prescription to Vyvanse, an analogous drug with a more gradually titrated release.

Each of these medication switches involved hours of scheduling, appointments, calls and trips to the pharmacy, not to mention significant amounts of money. Vyvanse, the medication I continue to take today, averages over $300 for a 30 day supply (the maximum amount a patient can receive at a time). The required psychological evaluation I participated in cost several hundreds of dollars.

I am very grateful to have health insurance and financial support from my parents, but many people do not have the same privileges, creating yet another obstacle for access to these radically life-improving medications.

Furthermore, because these medicines are controlled substances, practitioners are unable to prescribe them across state lines, which created quite the inconvenient nightmare when I stayed with my parents in Texas over the summer and winter breaks. Each time, despite coordinating with practitioners in both states beforehand, I had to stop my meds for weeks on end while I waited for my refill to get approved.

Given the concerning profile of these drugs, the matrix of restrictions to obtain them can arguably seem justified and reasonable. However, according to the current scientific literature, stimulant medications prescribed for ADHD are far less likely candidates for abuse than lesser or equally regulated drugs such as Xanax or Oxycontin, because ADHD medicines are relatively ineffective in those without a dopamine deficiency. The research article Prescription Stimulants in Individuals With and Without Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Misuse, Cognitive Impact, and Adverse Effects by Shaheen E. Lakhan and Annette Kirchgessner states, “The rumored effects of ‘smart drugs’ may be a false promise, as research suggests that stimulants are more effective at correcting deficits than ‘enhancing performance.’”

According to my experience and extensive research, these medications create a tangible positive difference in the lives of many individuals with ADHD. When I finally started Vyvanse, my life became coherent and manageable for the first time in years. I no longer struggle through my responsibilities in a distracted haze and instead easily find joy in my work, especially when encountering new challenges. I actually feel a sense of pride and satisfaction when I complete things now, as opposed to the feelings of exhaustion and numbness I had grown so used to.

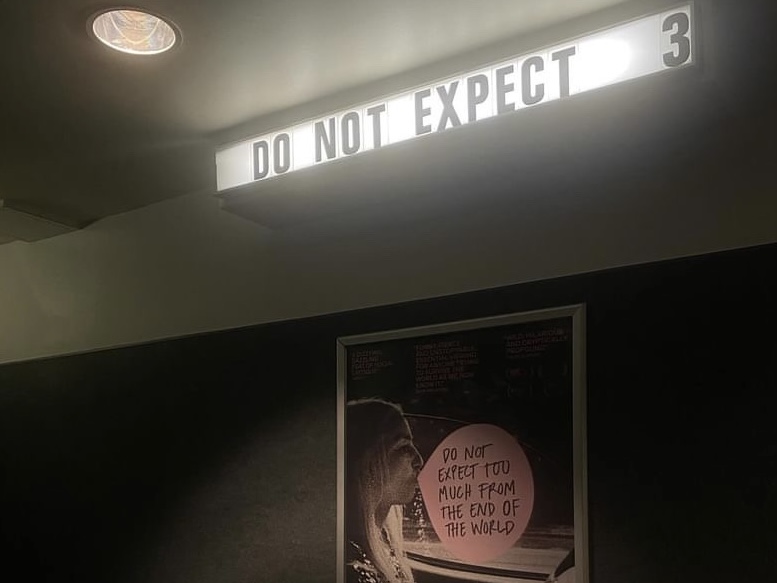

Unfortunately, these benefits and the vast others of this miracle medication are not guaranteed; they are contingent on my ability to continually meet a set of hyper-specific and shifting expectations, primarily due to the fear and restrictions surrounding stimulant medications. The stigma and misinformation surrounding ADHD medication, enabled by its classification as a Schedule II Controlled Substance, inhibits medication accessibility for those that most need it.