I. Faith as a foundation

The undergraduate student body of Seattle Pacific University is 60% ethnic minority, but diversity initiatives are disappearing.

In the spring of 2022, the Office of Inclusive Excellence, responsible for diversity equity and inclusion, was dissolved after director Sandra Mayo resigned. At the end of this academic year, the Office of Multi-Ethnic Programming will let go of its director, Joyce Del Rosario, and the position will remain vacant.

Both programs promote representation and inclusion throughout the university, OIEX working within the administration, and MEP in student life. The changes follow sweeping budget cuts, a 40% decrease in staff and faculty reductions following dipping admissions rates and a 2-year protest against the university’s hiring practices regarding human sexuality.

Under these circumstances, downscaling is inevitable; however, losses in diversity programming reflect a nonessential status despite student demographics.

From her inaugural address, President of SPU Deana Porterfield celebrated and affirmed the value of diversity.

“We will embrace a diverse and global world as we create a community that serves all people, modeling the beauty and diversity of life in God’s kingdom. We are blessed to have a beautifully diverse student body,” Porterfield said. “Can you imagine how our programs and practices can and will create opportunities for students to explore cultures, examine biases, and embrace the diversity of God’s kingdom? A place of belonging?”

The answer depends.

MEP has a 14-year legacy of helping underrepresented students navigate college, many of whom come from BIPOC, queer, DACA and first-generation backgrounds. Del Rosario has directed the program for two years, but when she arrived in the summer of 2022, it was not her first time on campus.

In 1991, Del Rosario was a freshman. SPU looked much different, especially for a Filipina woman.

“I grew up in Shoreline [Washington] and came here for my freshman year. I moved into third Ashton, and it was hard. It was a really, really white campus. I mean, I’ve grown up in Seattle, so I’m used to predominantly white spaces, but it was very different,” Del Rosario said. “It felt like I was in a J. Crew catalog – very preppy, white, clean-cut, happy, good-looking people. And I didn’t feel like I fit, so I transferred over to UW by my sophomore year.”

Directing MEP, in a way, is redemptive. Del Rosario can create the inclusive and supportive environment she did not have as a freshman.

“I love the students here. I’m gonna get teary as we go, but I freaking love the students here,” Del Rosario said. “That 1991 freshman would never have imagined SPU could be this.”

Today’s racial and ethnic diversity dramatically shifts the university’s narrative. SPU was founded by Free Methodist Pioneers in 1891. For over a century, it was a predominantly white institution, but in a little over two decades, the predominance has been undone.

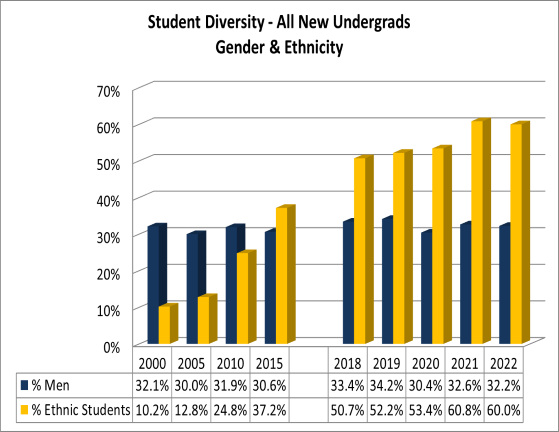

In the year 2000, the undergraduate student body was 10% ethnically diverse. Fast forward 22 years, and the percentage has jumped to 60%, according to the Office of Institutional Effectiveness.

Diversity happened intentionally, and a multitude of factors accounted for the change. But at its core, the motivation was theological. Diversity became part of SPU’s Christian calling.

DEI, often understood as a strategic organizational framework, has recently come under fire nationwide. However, unlike institutions in Florida, Tennessee and Utah, SPU affirms diversity. While metrics and benchmarks certainly contribute to the equation, diversity at SPU is not a data-driven “DEI” per se but a value motivated by faith.

According to the SPU Statement of Faith, “We believe that theological diversity when grounded in historic orthodoxy and a common and vital faith in Christ, enriches learning and bears witness to our Lord’s call for unity within the church. We are also well aware of other dividing walls that separate people from one another, walls that Christ desires to break down — walls of gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, language, and class.”

In other words, diversity stems from ecumenicalism, the idea that Christians, across all denominations, should work together towards unity and cooperation. Differences in Christian traditions are embraced, and SPU makes the intentional effort to diversify theological perspectives across the university.

However, there is a question of whether the value of diversity is upheld. If SPU wants to honor its motto, “Engage the culture, change the world,” it must be willing to engage and change itself.

II. Sowing seeds

Gary Ames, one of SPU’s most prominent donors, funded the Ames Scholarship and Leadership Program for ethnic minorities in 2001. The Ames Scholarship would be the first of many steps to both grow diversity and foster inclusion.

“We found Seattle Pacific a natural place to invest because of its vision for engaging the culture, because it is a quality Christian university — and because it has a diversity problem. For SPU to be relevant in the Seattle community, it can’t be 90 percent white… Today, 13 minority students at SPU are the recipients of Ames Scholarships,” Ames said in a 2002 Response article.

This paradigm shift happened during President Phil Eaton’s administration between 2000 and 2012.

The Rev. Tali Hairston was one of the key players in developing diversity work at SPU. In 2003, Hairston was appointed as the Special Assistant to the President of the University for Reconciliation and Leadership Development. He worked closely with Eaton, advising the administration and building nuance, justice and Christianity into the institutional framework of diversity.

“The initial question started with, ‘How do we impact the world around these issues if we’re not involved with the communities that are having these issues?’ One of the things that I was concerned about was how we engage these issues, intellectually and academically but authentically to the story of scripture,” Hairston said.

Diversity work began comprehensively. Throughout all departments, strategic hiring and restructuring led to rapid developments in student life, academics, admissions, resident life and administration. Hairston and other equally intentioned individuals permeated inclusion into SPU’s fabric.

In 2004, the John Perkins Center for Reconciliation, Leadership Training, and Community Development (JPC) was formed in partnership with civil rights activist and theologian John Perkins. Hairston was appointed as director of the JPC and reported directly to Eaton.

MEP was introduced in 2008 with the help of Vice President of Student Life Jeff Jordan. In 2011, Vice President of Academic Affairs Les Steele recruited Brenda Salter McNeil to spearhead a reconciliation studies program within the theology department.

“We had key people in admissions, key people in HR, key people throughout the university who we had hired and developed over several years. We had academic programs, we had Dr. Brenda Salter McNeil, we had all these key hires that had happened between 2004 and 2012, so we were pretty deeply rooted,” Hairston said. “Essentially, we could go on autopilot and still be successful. Of course, between 2012 and 2018, a lot changed in those six years.

In 2012, Eaton stepped down as president, and President Dan Martin was inaugurated. The torch was passed, but its bearer led slightly differently.

Martin switched SPU to a provost model. The JPC was placed under University Ministries, away from its administrative impact, and in 2017, the OIEX was founded with Sandra Mayo as Vice Provost of Inclusive Excellence.

The commitment to diversity would be maintained by the deeply rooted staff, faculty and programs established before Martin; however, Hairston believes that the new president needed to do more to take initiatives further. For five years between Martin’s inauguration and OIEX, diversity initiatives stalled.

“I do feel like we wandered in that period,” Hairston said. “What do we do from here? [After] conversations with the president and the provosts about how to move forward, they chose a particular direction, which was the development of the Office of Inclusive Excellence. And at that point, that’s when I left.”

The desire for a DEI office was not initiated by Martin or his administration. In 2014, 18-year-old unarmed Michael Brown was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. The event stirred national unrest, and conversations about race and injustice found their way onto SPU’s campus.

It inspired students to evaluate the structure of their university critically, and in 2016, the SPU Justice Coalition was formed by students to advocate for change.

According to the SPU Justice Coalition website, “We – a united group of Seattle Pacific undergraduate and graduate students, alumni, and community supporters – in an effort to hold the University accountable to those values and convictions which it espouses to be fundamental to its identity, demand that the following items be implemented.”

The Justice Coalition petitioned for a chief diversity office, academic credibility requirements, job training and a restructuring of the hiring policy. Martin listened to the campus and incorporated these changes. He hired Mayo, instituted OIEX, and implemented the Cultural Understanding and Engagement curricular requirements.

This was a victory for the Coalition, but the movement’s spirit and students soon graduated. SPU did not change enough for OIEX to stay.

The grassroots justice of 2016 would allude to future tensions. In 2021, SPU was sued for discrimination, and Martin stepped down as president.

Even Eaton, who championed racial and ethnic diversity, had no answer to the question of human sexuality.

III. Terms and conditions

Madisynn McCombs Encinas was Sandra Mayo’s executive assistant. From the beginning of 2021 to the end of 2022, she worked for OIEX during the student protest against the board of trustees.

Initially, OIEX gained traction by workshopping departmental diversity plans, creating the Search Advocate Program, and the Timeline of Diversity at SPU. But when McCombs Encinas arrived in 2021, the impact of OIEX was reduced.

“At the time, Dr. Mayo was reporting to the president, but while I was working in the provost’s office, she was moved to reporting to the provost. I see that very much as a demotion [because] you’re moving down in the university hierarchy,” McCombs Encinas said.

Originally, OIEX was called the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, but the name was changed because of a systematic restructuring. Mayo started reporting to ex-Provost Laura Hartly instead of the interim president, Pete Menjares. Hartley was fired in May 2023.

The office never grew beyond Mayo and McCombs Encinas; however, OIEX did not disappear because it lost support. In May of 2022, Mayo voluntarily gave her resignation. McCombs Encinas cannot speak on Mayo’s behalf, but working together closely, she had felt Mayo’s burden.

“Students have very high expectations because they have these hopes and dreams of what a really inclusive and diverse campus could look like. The administration might have hopes and dreams about what that could look like. Faculty, staff… But one office can’t make all of that happen. You have to have collective buy-in. It can’t be from just two individuals,” McCombs Encinas said.

DEI leadership is notoriously a burnout position (the article features a brief comment by Mayo). There is fatigue and emotional labor. After the George Floyd protests, expectations grew higher, but corporate commitments have nationally dwindled. Working against generations of systematic injustice and cultural biases is not easy, especially if DEI leadership lacks resources and personnel.

At the crux of a student protest advocating for queer voices, OIEX found itself caught. How could it work towards inclusivity if the university was facing backlash for being exclusionary?

“I think it just became next to impossible for her to do her job in a way that would be authentic to herself and also [do] her job with integrity,” McCombs Encinas said. “For Dr. Mayo, ‘How can I be the head and representative of an office that is literally called Inclusive Excellence… and yet we are forced to exclude certain people, lots of people, from the table.’”

Part of the reason Hairston left SPU in 2018 was because he knew comprehensive diversity and inclusion was failing. It would only ever be about race and ethnicity.

“By the time I left, critical conversations were happening across campus that moved the conversation from race to sexuality,” Hairston said. “It was not a straight shot from ‘Let’s talk about race’ to ‘Let’s talk about sexuality.’”

Hairston believes SPU kept its head under the sand. Eaton committed to racial justice and ethnic diversity, and Martin maintained this, but when the campus demanded recognition of sexual identity and gender orientation, the university drew a tight lip.

The LGBTQ+ workgroup, composed of board members, faculty and staff, worked for an entire year to negotiate a solution. Eventually, the workgroup reached a third way, but the efforts were made fruitless when the Free Methodist Church threatened to disaffiliate with the university almost immediately before the final vote.

In May 2023, the board of trustees decided that it would not change its statement on human sexuality or its hiring policies. Interim President Menjares, a person of color, became a punching bag for campus criticism. Menjares left, and the university hired its first woman president.

Bodies matter. Representing both colored and female leadership paints progress for the university, but its lack of queer affirmation begs the question: does diversity and inclusion have an agenda?

“If we say we mean diversity, even ecumenical values on campus, if we say that’s part of who we are, yet [exclude] people… then do you really value true diversity? Or is it diversity on your terms?” McCombs Encinas said.

During the student protests, a survey conducted by the Associated Students of Seattle Pacific (ASSP) showed that 75% of faculty, 73% of staff and 86% of both graduate and undergraduate students objected to the employee sexual conduct policy.

People of different backgrounds are attracted to SPU because of its diverse campus. Programs like JPC, MEP and OIEX represent a collection of identities. However, queer coworkers, theologies and discourses are excluded from a campus that claims to be ecumenical and inclusive.

“The campus that they came to know and love is still deeply rooted in the university even though the tree tops have been cut off,” Hairston said. “I wish evangelicals would have an understanding of sexual identity and gender orientation that would allow for less conflict and more growth and development, but that’s not been the case.”

IV. Misalignment

Diversity is both a quantitative reality and a qualitative aspiration.

The Eaton administration’s holistic actions to build lasting programs reflected an aspirational desire for diversity. This led to a posture of racial and ethnic inclusivity, but in its early days, it lacked a quantitative number of diverse students. Today, the student body is 60% diverse, but that initial qualitative value has withered as its initiatives lose commitment.

Reality and aspiration have yet to be aligned, and the opportunity was missed after the board’s decision. So, does SPU value diversity? The spectrum of commitment might be “yes” for some and “no” for others. One can tap into both morale and finance for an answer.

When Gary Ames passed away in 2021, SPU lost his financial support. It began with an initial $1 million dollars to support students from underrepresented racial and ethnic backgrounds; after 20 years, this became nearly $8 million dollars donated to the university for various causes.

Even if the Supreme Court ruled affirmative action unconstitutional, the reallocation of scholarship money could support other programs under MEP.

The Ames dollars funded MEP programs like Early Connections, an orientation program that helped transition incoming minority students to campus life. While the university funded MEP’s operational and personnel costs, Early Connections and scholarships depended on outside sources.

Del Rosario believes MEP depended too heavily on these donations, inflating the university’s commitment to diverse students.

“When I’m talking about support, the important thing to me is this program has been around long enough [so] that there should have been more institutional dollars given to the program to grow it [without] depending on one family to keep it going,” Del Rosario said. “We rested on our laurels. And as soon as one part fell under us, it all fell apart.”

Yes, global pandemics and student protests severely affect budgets, but turbulence tests integrity. MEP is a 14-year-old program. There was time to diversify funding and institutional investment, but that did not happen.

Beyond student life, a similar circumstance is reflected in academics. Dr. Brenda Salter McNeil is a well-known expert on racial reconciliation studies at SPU. She began her career when Martin became president in 2011.

In 2010, SPU acquired a 3-year seed grant from the Stewardship Foundation, and VPAA Les Steele recruited McNeil to develop a reconciliation minor. The grant would fund the program, and the university would fund the professor, but McNeil was initially unaware of the funding.

“I did not know when I was recruited that the funding they received for the stewardship foundation was a three-year seed grant. Nobody said to me when I was living in Chicago, ‘Would you come here for three years, and that’s how much funding we had? ‘ Because I would’ve said no. I’d still be in Chicago in the house I had bought,” McNeil said.

McNeil remains at SPU. Her passion for students and reconciliation justifies her stay, but there is more to be desired from the university’s promises.

“I think SPU has given the impression that [diversity] is something they are completely committed to. But if you follow the money, the money doesn’t come from SPU. It comes from outside sources who are connected to SPU,” McNeil said.

For 13 years, the reconciliation program has remained a minor degree. Growth requires grants, and McNeil is solely responsible for acquiring additional funding. But McNeil does not want to be a fundraiser; she wants to teach.

“It really does feel like usury. It’s not really a reality that diversity is a core value concern. It feels as if you recruit under false premises,” McNeil said. “What SPU is is an aspirational university that presents the image of who they want to be. However, it is portrayed as if it is who we are.”

Aspirations are easy to say but hard to pay, and they are difficult to actualize. Budget cuts and fleeting donations weaken a community, but when push comes to shove, only the most valuable pillars of commitment will remain. OIEX is gone; MEP lost its director; diverse faculty must prove their justice programs; students lose hope when their campus does less for them.

“[Aspiration] may get the person here, but it does not create a climate or campus culture of inclusivity where everyone brings their true authentic full self because they really do believe that this place is what it says it is. And when you start coming to the conclusion that this is transactional and not transformational, then you commute,” McNeil said.

The relationship one has with their institution becomes a degree; it becomes a paycheck. Students, staff and faculty of diverse backgrounds are less inclined to invest in a community that does not invest in them. With aspirations that are not holistically true, the burden of proof rests on those who were sold that vision.

“The burden of proof. Yes, I think that’s where we are… It’s more [of] a vision. And you’re supposed to give yourself sacrificially for this vision that, over the course of decades, you don’t quite see become a reality. That’s hard to do,” Salter McNeil said.

The dream is tired and weary. Protests have quieted, and community leaders have either graduated or parted ways.

Still, the university is 60% ethnically and racially diverse. Though specific initiatives have crumbled, SPU continues to try.

V. Doing a new thing

From 2001 to 2012, Les Steele was the VP of Academic Affairs. Under Eaton, Steele worked with Hairston to lay the groundwork for many early diversity initiatives. As of Fall 2023, Steele has returned as the interim chief academic officer.

“Dr. Porterfield has announced that there will be a half-time position of a faculty member who will serve as a special advisor to the president. That person will sit on the president’s cabinet and other places and choose to speak in, to be intentional,” Steele said.

The position’s title will be the Special Advisor to the President for Diversity and Belonging and will be given to a current faculty member. Half of their role will be compensated as the special advisor.

A finalized job description lists objectives to “give direct attention to the institution’s policies, practices, structures, climate and culture through the facilitation of diversity initiatives, services and resources designed to support students, staff, faculty and administrators in advancing diversity and belonging in all aspects of the campus.”

This position’s primary duties reflect similar OIEX goals, adjusting preexisting programs like the Search Advocate Program, Faculty Diversity Committee and the University’s Diversity Plan. However, Steele’s outlook for the position is somewhat bleak.

“In higher education, if you’re appointed as a special advisor to the president, it’s not a good spot. Cause you have little influence, little direct authority over anybody. So, you have to be cautious in the way you do this,” Steele said.

This position is much different than Hairston’s role as Special Assistant. While similarly intentioned, special advisor is a two-year appointment for a part-time position to fill the gap of an entire vice provost office. It raises concerns about resourcing, impact and burnout.

“This may not be a common term or one that may sound more derogatory than positive, but it is a gadfly. You’re sort of looking and watching, sticking your nose around. And I think metaphorically, that’s what President Porterfield really wants,” Steele said. “That almost sounds negative, like a tattletale, but it really is being aware of how you continue to move and keep reminding and bringing resources to the table.”

Steele’s account of the position is part of Porterfield’s inaugural imagination for “programs and practices [that] can and will create opportunities for students.” The burden of proof falls on the special advisor to meet the expectations of students, staff, faculty and Seattle.

Budgets and structure for the 2024-2025 school year have yet to be announced. An official announcement will arrive after the spring quarter ends and students leave campus. The special advisor interviewing process begins around May 31 and will be selected for fall 2024.

2024’s academic theme is “God is Doing a New Thing.” SPU is an old school. Porterfield and her administration will be the ones to tell the story of diversity, faithfully or not.

President Porterfield chose to comment via email:

What does diversity mean to you?

“When I think about diversity, I immediately think about God’s creation and how we are each a reflection of him. I believe we are all created in God’s image. When I think about diversity from a leadership perspective, teams are stronger with greater representation in discussions and decision making.”

What does diversity mean for Christians?

“While I can’t answer this question for all Christians, I will answer by saying what diversity means to SPU, as stated in our Statement of Faith. The fourth pillar of our Statement of Faith is that we are genuinely ecumenical. Our ecumenical understanding is anchored in the historic orthodoxy of our first pillar, but recognizes the depth and breadth of our faith. Ultimately, it calls us to unity in Christ. I will quote one of the sentences from the statement, as it sums up SPU’s commitment very well. Thus, in all of our diversity, we are centered in Christ, and called by him to shape, model, and participate together in grace-filled community.”

What does diversity mean for the university?

“During my inaugural address, I listed five commitments that will shape our work in creating the next season of great opportunity for Seattle Pacific. One of the commitments is to “embrace a diverse and global world (access for the next generation) as we create a community that serves all people, modeling the beauty and diversity of life in God’s kingdom. We are blessed to have a beautifully diverse student body, and SPU is one of the more ethnically diverse campuses in Washington state.”

“As the university continues to reposition itself for the future, we are committed to supporting our diverse student body. We have been without a vice president for two years and there have been decisions during budget adjustments that have impacted the structures. Currently we are re-envisioning a new structure of support for our students within Student Life. Also, we are now reviewing applications from faculty for a new special advisor for diversity and belonging. The position will provide strategic direction to the University’s diversity and belonging efforts, sit on the President’s Cabinet, and report directly to me. Looking forward, the university is committed to both diversity and belonging of all our students, but we also recognize a need for intentional voice and support for our students, faculty, and staff.”

L • Jun 22, 2024 at 3:40 pm

This is an amazing piece, thank you for your work.

Jim Ballard • Jun 4, 2024 at 2:02 pm

It’s true-God’s creation is diverse, including mankind. Yet mankind’s relationship with God was damaged by man’s sin. In grace, God sent His Son to solve our sin problem. That solution presented in the Bible is faith alone in Christ alone (i.e.-belief and trust in Jesus Christ’s credibility, death, burial, resurrection and ascension).

This article by Lim only emphasizes his perceived value of diversity as it relates to the university supporting the student needs of diverse cultures (entitlements). Really?? Diverse cultures will always have different perspectives, priorities, and disagreements.

Seems like SPU ought to be focused on providing a Christ centered education that enables students to find career opportunities that meet their educational priorities and financial needs.

If the students can’t find that at SPU, or feel like they don’t fit in, maybe they should find another university. This idea that “diversity” and “entitlements” outweigh merit and accomplishment is foolish and misguided.

It is SPU’s responsibility to determine the school’s curriculum, and hire the best professors to teach that curriculum.

It is not the responsibility of SPU to make the students feel like they fit in. Rather, it is the student’s responsibility to demonstrate his/her ability to learn and achieve his educational goals. If they feel like student life is unfair, gee I’m sorry but life is unfair. So get used to it and put forth the effort to make yourself successful.

Zeapoe • May 15, 2024 at 11:05 am

Phenomenal work on this article.

It is important to document these changes in SPU’s journey towards a more authentic commitment to diversity and inclusion. As they say, change is slow but I’m happy to see the students haven’t given up!