College is changing

Variety of reasons alter mindsets, statistics on both national, local level

May 3, 2023

Due to a variety of reasons, the mindset regarding attendance and value of university has shifted recently. On a national level, college attendance is down, and skepticism regarding higher education is up. Every individual university is affected differently, including Seattle Pacific University.

For SPU, national trends join local issues to affect enrollment, transfer statistics and general student mentality. Stephen York, associate director of undergraduate admissions, acknowledges the COVID-19 pandemic as a potential catalyst for changes in college realities.

“There’s a lot of different things at play. On one hand, you’ve got COVID that’s been directing people,” York said. “You’ve got this societal skepticism, people stopping and thinking whether a college degree is still worth it.”

This mindset change, as broad as it is, cannot be attributed only to the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent impacts on the way people view higher education in the US are various and extensive – pandemics, economic recessions and changes in demographics all play into the bigger picture.

Mark Sullivan, the director of SPU’s Academic Support Center and academic counseling, has been with Seattle Pacific for 16 years.

“Economic reasons, who the students are that are coming to school and what students are looking to get out of college have all changed,” Sullivan said. “That seems like a natural progression.”

Universities are not faced only with this mentality switch. Physical numbers of college attendees will be drastically affected by a growing skepticism for higher education, the approaching “demographic cliff,” which, due to low birth rates during the Great Recession, means that the college age populace will decrease rapidly.

“As we look at big national trends – fewer students going to college, the demographic cliff coming in a few years – and conditions on the national level, there are just fewer students going to school,” Sullivan said.

This change in university realities looks different at every type of college in the U.S. SPU, a private, 4-year institution, prioritizes community and largely expects students to cycle in and out of the college as a united class, with the same number of students. However, one of the changes in university life at residential schools has been a larger reality of students transferring in, out and around different colleges.

Transfer swirl is when students – “swirlers” – transfer from institution to institution without completing a degree first. For schools like SPU, swirl and large numbers of general transfers are unexpected, as explained by Sheila Steiner, the Assistant Provost for SPU’s Office of Institutional Effectiveness.

“Schools that are traditionally residential, where we try to create this experience for students coming directly out of high school to come and live and be part of the community are – or were – outside of that,” Steiner said.

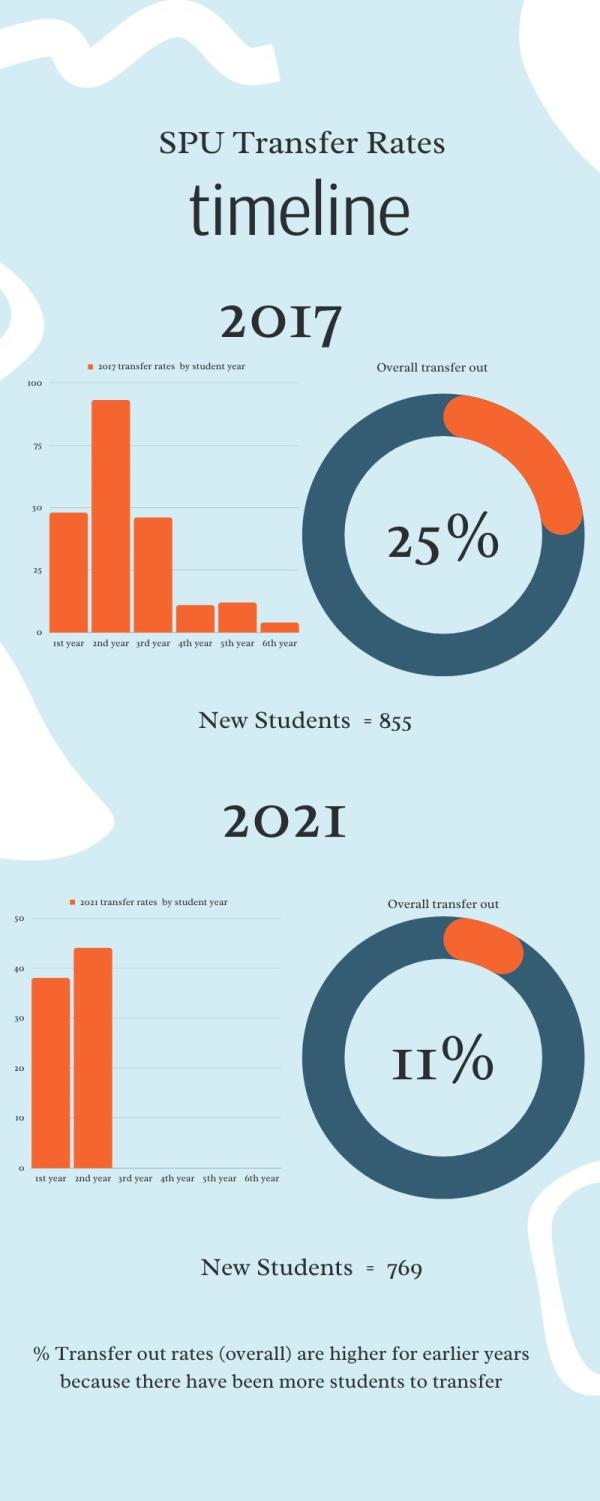

By 2022, classes that entered SPU in 2017, 2018, and 2019 lost 25% of their original population to transfer-out, and incoming undergraduate classes from 2018 to 2022 were about 20% to 25% transfer-in. This newly large reality could be the result of COVID-19 or other national trends.

“We’re not a transferring institution. We don’t expect students to transfer, but the pandemic may have changed that,” Steiner said. “I think swirl is more common when you have fully online programs.”

Hypotheses for why transferring has become a more normalized option are various. For SPU specifically, students’ reasons for transferring out or not attending range from national trends to hyper specific experiences. SPU no longer offers online courses or individual course scheduling, only has so many programs and hosts a unique Christian identity.

“There are also students who just can’t afford a private school. I’ve had students have great financial aid packages, but there is a skepticism on taking loans or more heavy debt,” York said. “By a very natural process, you have students who say, ‘Oh, that’s actually not what I’m looking for.’”

First year Summer Connell will be transferring out next year due to multiple concerns specific to her experience at SPU.

“There were a lot of things that went into play,” Connell said. “I’m going to be moving back home, and I’m hoping to go to cosmetology school, but I need to recoup some costs. The costs, the concerns of the lawsuit, the worse Gwinn gets. I have multiple food allergies, so it is hard for me to eat there.”

There are countless reasons for students to transfer out of SPU or any general university, especially with national trends and local issues.

“The narrative is that the board’s decision about the hiring policy may have impacted students’ willingness to stay, plus with impending program changes, there’s a lot of uncertainty which could prompt folks to look elsewhere,” Steiner said.

While transferring is not greatly expected at schools like SPU, there are structures in place to help students get where they need to go.

“There are lots of spaces and opportunities for students to move around, maybe in ways that didn’t exist before,” Sullivan said. “It’s just a good market for students to have more options.”

Staff members at SPU working in admissions, academic counseling and other recruitment and retention services aim to give all students coming into SPU a sense of community, whether they’re straight out of high school, from different universities or giving higher education another chance.

“One of the things that I really value in my role is that sense of belonging,” York said. “Oftentimes you have transfer students who have some reason that they left their institution and are looking to go elsewhere, or if it’s somebody coming back and wanting a second chance at an education – maybe a senior citizen – that relationship is going to be important to their success.”

For students transferring out, the work is often with the university they are headed to, but academic counselors at SPU are a space to navigate credit loss, geographic change and general success.

“We often meet with students who are thinking about transferring, knowing they’re going to transfer or have already transferred and have questions. Maybe a major hasn’t been a good fit right, they haven’t found success in certain courses, or they’re just not sure it’s the right spot for them,” Sullivan said. “We can be a good first stop for students who are in that space.”

National changes in mindsets, population and realities for higher education institutions join local, specific issues to affect SPU. Structures, students and numbers will continue to change.

“Higher education has been sent so many waves and ripples,” York said. “We’re still waiting to see what happens.”