Cogito, ergo sum

Students explore the mind-body problem

May 4, 2022

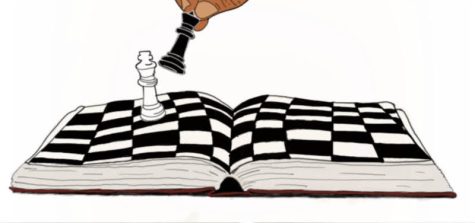

A mirror will not be honest. One looks to see the substance of their face, their eyes, their hair and their shape; and they will see what others see. Yet, a mirror is only physical and fails to break the tension that separates the mind from its body. It does not reflect consciousness. It does not reflect feelings. And it does not reflect the mind.

Yet consciousness and thought are phenomenally real, and between the immaterial mind and the material body, there is a relationship. This presents the mind-body problem: how separate are they? For students at Seattle Pacific University, answering this question is an attempt to understand and nurture the nature of themselves.

Second-year psychology major Wesley Joo believes that both mind and body are two sides of the same coin. While the coin suggests a whole, the sides suggest one can lose the other.

“There is a distinction between someone who is physically there and someone whose mind is there, literally present and conscious, and they are themselves,” said Joo. “I have personally seen people who are brain dead, patients who used to be people that I knew. I can see them, and I can touch them, and I can feel the warmth of their hand, but I know the only thing keeping them alive is a machine.”

A body can be observed without its mind, but a mind is difficult to observe without its body.

Dr. Philip Baker is an assistant professor of psychology and a neurobiologist. Baker would say that Joo believes in substance dualism, an idea invented by René Descartes that suggests the mind and body are two different things and can exist apart from each other.

“A substance dualist would say, ‘No, there is a non-corporeal part of you which is your mind or your soul, which can leave your body, say, after you die.’ I tend to think that probably isn’t true,” said Baker. “But another way of asking it is, ‘Is there more than the physical?’”

Neurobiology has allowed us to propose that the mind is physical because the brain is physical. But this is a theoretical reduction. Regardless, if this is literally true, it does not disregard the mental and physical sensation that they are two separate entities.

The difference between physical and mental health presents realistic implications of the mind-body problem.

Haley Marlow, a second-year business marketing finance major, plays on the SPU women’s basketball team. While physical performance is an athlete’s apparent objective, Marlow stresses that athletics is also a mental game.

“You have to think so much… Thinking of plays, running around, where am I going to go next, what are they going to do, what’s the defense going to do, where do I need to go?” said Marlow. “And some stuff is natural, it’s just subconscious, like, ‘Oh, I’m running,’ ‘Oh, I’m breathing,’ but other stuff you can get so scared…Your brain is telling you, ‘Don’t miss. Don’t miss. Don’t miss.’”

Life presents Marlow with a physical task, but the strength required for her success often seems largely dictated by the mind. Think of the placebo effect.

“That’s what KT tape is for, have you heard of that? Like the stuff athletes wear? A lot of it is a placebo. And you can ask trainers about it. Some of it does help with inflammation and swelling but a lot of it is just the thought of it there. Your brain is like ‘Oh, there’s something helping my pain,’” said Marlow.

But mind over matter has its limitations.

“You don’t want to necessarily end up like Steve Jobs and believe that your mind can heal you of cancer, because it’s incredibly likely that Steve Jobs would still be alive today had he not approached it from a more mental standpoint,” said Baker.

The body is not debated upon, because it is simply there. The struggle with defining the mind reflects the struggle to assign mental diagnoses and treatments. It is not measurable, and it is not observable like an x-ray or blood test.

“One of the hardest things to say to someone, for instance, who has depression, is honestly the best thing we know for depression is exercise. But there are several reasons why that [might] not be a great message to give to someone,” said Baker.

No mirror is magic enough. As one stares into its depths and asks a question of mind, body or more, they realize that what they receive is not an answer; it is their reflection, and their reflection cannot help but ask a question too.

The mind-body problem is a problem that speaks for all problems. But it is also a relationship that proves both are in it together.

“I view everything very holistically and that you don’t really have good health unless your body is well, your mind is settled,” said Joo. “So I guess, I would describe health as balance.”