Uncovering assumptions, taking accountability as viewers

Naomi Hume explores uncommon notions of femininity

October 31, 2019

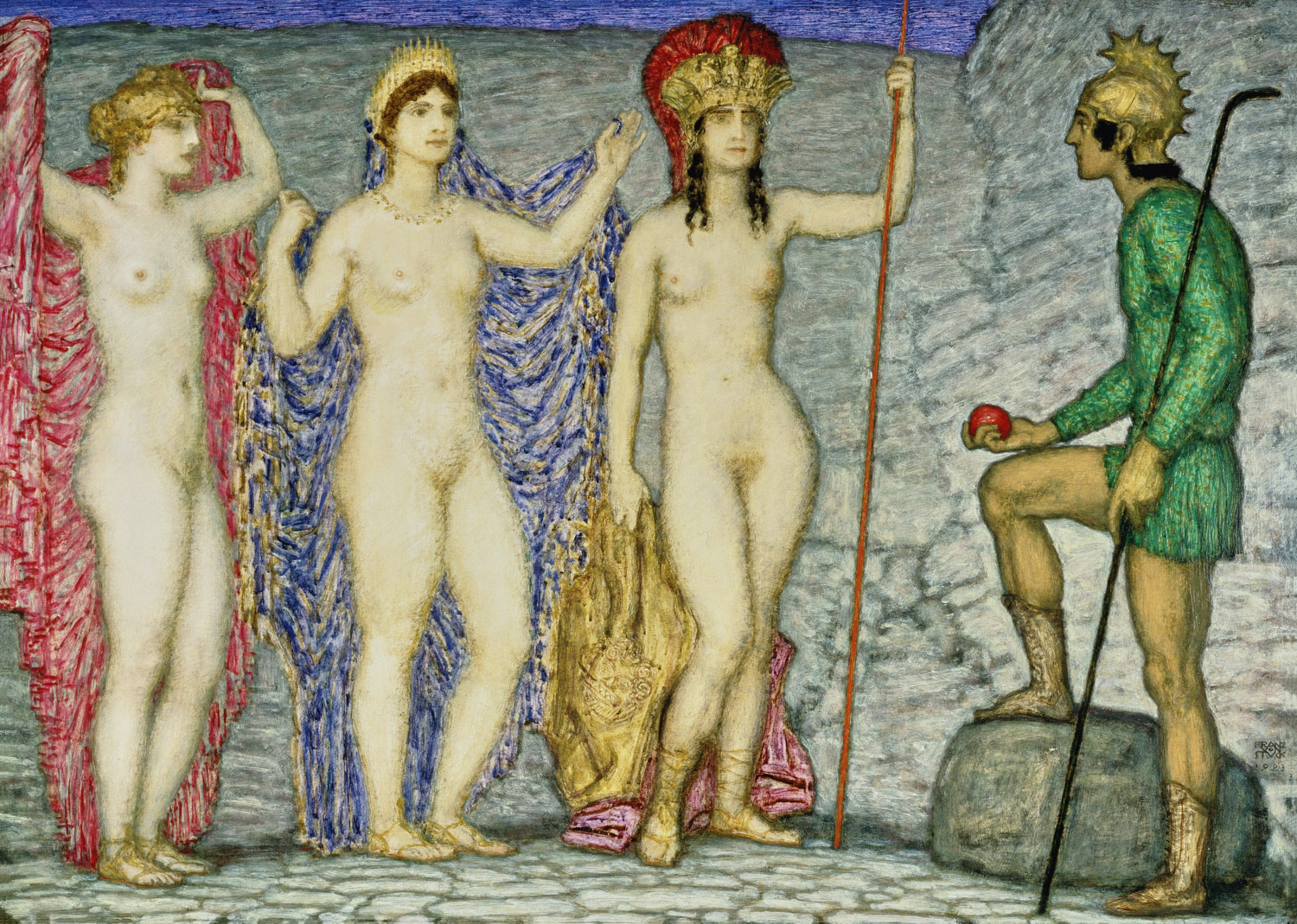

Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.168.

People gather around as guest curator, Naomi Hume introduces her gallery at the Frye, entitled “Unsettling Femininity,” with a painting called “The Judgement of Paris” by Franz von Stuck. The painting depicts three nude women being judged by Paris, the Greek legend.

Hume, an art history professor at Seattle University, started the series with this painting because Paris is deciding who is the most beautiful between the goddesses Hera, Aphrodite and Athena; they all stand in front of him naked.

The story illustrates how women’s bodies are often viewed as objects to be judged by men.

“The exhibition asks viewers to reconsider the very act of looking — in all its positive and negative connotations,” said Hume during the tour.

“In doing so, it offers an invitation to unsettle and unpack these enduring, and often unquestioned, notions of femininity.”

Hume’s intent for this collection is to challenge the viewer to take personal accountability for the way they perceive femininity. By this, she means that the objectification of women lies in the viewer’s hands — and not at the fault of women.

Gabriel von Max. The Christian Martyr, 1867. Oil on paper affixed to canvas. 48 x 36 3/4 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.116.

Hume argues that society’s interpretations of women are rarely challenged and women are accepted as objects to view. So, she offers the viewer a new way to look at women.

“There is an unspoken assumption that men actively look, and women are objects to be looked at,” said Hume.

Hume organizes her curation in four themes: judgment, morality, performance and artifice. She wants the viewer to use these themes as a new lens through which to view the classic pieces of the Frye’s collection.

The first collection of paintings in the theme of “judgment” was curated in order to make viewers feel a sense of conviction. The viewer is asked to recognize the way women are often portrayed: white, and sights to be looked at and judged.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Susanna and the Elders, 1866. Oil on canvas. 64 5/8 x 46 5/8 in. Founding Collection, Gift of Charles and Emma Frye, 1952.199.

“Susanna and the Elders” by Franz Xaver Winterhalter depicts two men hiding behind heavy foliage, spying on a nude woman. She is making an attempt to cover herself as she looks out at the viewer outside the frame with fear in her eyes.

She makes eye contact with the viewer, invoking a sense of guilt because just as the men behind the foliage are clearly looking at her without her consent, so is the viewer.

“I want you to ask, what are you doing or thinking when you look at women,” Hume said.

The second category is “morality” and critiques the way that many artists use femininity to symbolize the morals of truth and purity. Contrarily, femininity is often seen as a way to tempt men into lustful sin.

The viewer should consider who may be accountable for imposing these harmful feminine ideals.

“This theme raises complex questions about the morals and motivations of viewers both inside and outside of the frame,” said Hume.

“The Gypsy Camp” by Ludwig Knaus depicts a woman breastfeeding her child, while men peer from behind a tree to try and get a glimpse of her body.

“The simple act of viewing can sexualize even the most commonplace behaviors,” commented Hume.

Now knowing that women are often viewed as objects, the viewer is provoked by Hume to question if the women in the paintings know this.

In the third theme, “performance,” the paintings depict women in the act of performing their gender roles.

In this collection, “Geraldine Farrar” by Friedrich August von Kaulbach and “Eleonora Duse” by Franz von Lenbach are two paintings side by side. To the viewer, something is off. Both of the women are intently staring at the viewer, something culturally frowned upon in the era of the 19th century.

These women are actresses playing a role. Their dramatic poses give them a sense of femininity but their stare makes the viewer feel unsettled. The viewer then questions if the women are performing what they have learned is expected of them or if they are being their natural selves.

“These paintings go against common notions of women’s roles in society,” Hume said.

The fourth theme, “artifice,” meaning unrealistic, critiques the “ideal” woman by pointing out the imposed constructs of beauty and femininity.

“In this time period, women were required to be beautiful in order to find a husband, and finding a husband gave them status,” Hume said.

She challenges the variety of gender roles imposed upon women in the 1800s-1900s and that perpetuate the perception of women in the modern-day.

“Muter und Kind” by Gabriel von Max illustrates this by portraying a caregiving mother in a light of sexual purity.

Women are expected to be virgins in order to remain sexually pure. By being a mother, the woman in the painting is no longer fits within this expectation. Hume illustrates that women are stuck between two societal expectations that are impossible to meet.

Hume implies that a key way to alter unfair perceptions of women is to hold the viewer accountable for sexualizing or romanticizing female identities. The collection posed an important critique of the way dominant notions of femininity are simply accepted by society.

Each painting is thoughtfully placed in order to complement or juxtapose the paintings around it. This puts the viewer in the position to think critically about the gaze of the artist and how the viewer participates in that gaze.

“There are many constructs put onto women, and it is our job as viewers to question those constructs,” said Hume.

“Unsettling Femininity,” curated by Naomi Hume, will be showcased for free at the Frye Museum through August 23rd, 2020.