By Kim See | News Editor

While pursuing his Foundation in Music Certificate from the International College of Music, transfer student Adam Colling lived in Kuala Lampur Malaysia from January 2016 to June 2017.

His favorite part of living there was the night life; the food stalls and other street vendors were open until anywhere between midnight and 5 a.m., which he took advantage of as a college student living abroad. In Malaysia, he experienced the culture, seeing what was similar with America and what was different.

While he does not want to speak for the entire country, especially since the majority of his time was spent specifically in the capital Kuala Lumpur, he said, “a lot of similarities between Malaysia’s masculinity culture and America’s,” such as an emphasis on financial success, men’s style, cars and other material things.

“A lot of things I noticed as being common between the two cultures were much more prominent in Malaysia than what I’ve experienced in America: popped collars, acting ‘above’ service workers, swearing in English, etc., were often seen as being ‘cool’ or ‘manly,’” he explained.

Globally, masculinity and the portrayal of it has evolved and continues to evolve. Between the rising trend of men being objectified in mainstream media, and the discussion of what it means to be a man in modern society, there is a fine line men find themselves walking on.

“Any environment that stifles emotional connection, and disparages groups of people is, I think, a broken system because it ignores such a large part of the human experience,” Colling said.

Here in America, he believes that society’s views on masculinity are changing, but too slowly. To him, the characteristics that make a good man are characteristics of simply being a good human being.

“A man should be kind, loyal, proactive and should think critically. A man should exercise patience. A man should know his limits and how to push them, and should learn how to deal with uncomfortable situations with poise and grace,” he listed.

But many of these things are not prioritized in larger society, Colling added. Society reveres the man who can financially handle everything in his household with little or no help, Colling said.

He noticed that some of his virtues are being cast aside in favor of other emotions and behaviors, such as anger and aggression. Part of this mentality, he believes, boils down to something very simple: it is easier to idealize violence, control and aggression than it is to sit in the discomfort of their consequences.

Many times on mainstream media, such as television shows or movies, audiences are entertained by two groups of men battling each other or a favorite action star entering the scene with guns blazing, Colling describes; yet those same audiences rarely see that same action star facing the families of those he killed, because violence sells better than watching a man deal with the consequences of his actions.

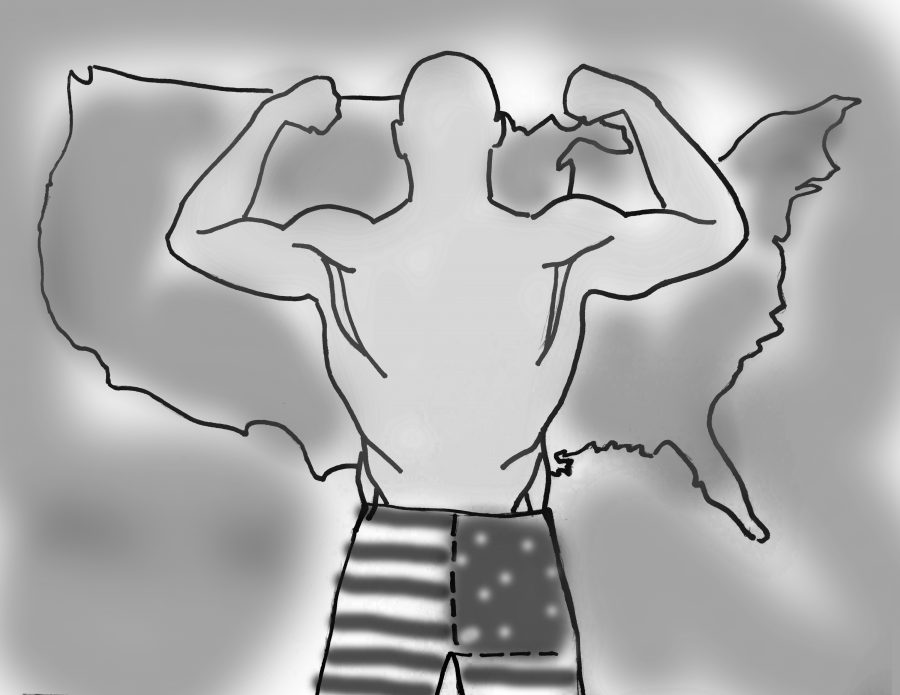

While it is true that there is a spectrum of male appearances on the big screen — rotund men, balding men, etc. — Professor of Sociology Jennifer McKinney points out a “narrowing of men who are kind of hypermasculine: very buff, very fit.”

“Just like with women, as men see more and more objectified images of themselves, they more and more feel like that’s who they’re supposed to be,” McKinney explained.

A CNN article called “Why Girls Can Be Boyish But Boys Can’t Be Girlish” by Elissa Strauss, which McKinney read and recommended, highlights the idea that gender progress is a one-way street towards the masculine. In Disney, for example, Strauss mentions “macho or strong and brave” female characters such as Pocahontas, Mulan and Moana. Their male counterparts, however, continue to alternate between “brute and naïf.”

“Men actually have to walk, in some ways, a finer line because their box is smaller,” McKinney said.

“Women are in the workforce, women do wear pants and jeans. Women compete in the same sports men compete in, but men cannot do anything that is ‘feminine’ or else that is considered really breaking the cultural rules.”

She goes on to explain that masculinity, however, is not a biological expression but a societal expression.

In the typically thought of hunter-gatherer societies, men are depicted as the hunters and women as the gatherers when in reality, both hunted and gathered. The difference was men explicitly hunted big game because they were expendable.

If a male hunting party ran into a warring tribe or accidentally ate toxic vegetation, if they all somehow managed to fall off a cliff, and only a couple men survived or were left in the tribe, the tribe would survive because even just a couple men have the ability to populate an entire tribe, McKinney explained.

But people tend to assume that the way things are currently are how life works naturally, she continued. This is false, as is the idea that masculinity over time is a linear construct, when in truth, it is constantly changing over time both within and across cultures.

She and Assistant Professor of History Rebecca Hughes, however, explain that society’s current ideas of masculinity can be traced back to the industrial revolution.

This was when masculinity largely became associated with work. Manufacturing jobs and manual labor became associated with men, because men were thought to be stronger and more capable to do the job.

Empire became a way to live out these masculine ideals, Hughes explained.

In the time of Hitler, for example, being a man was greatly associated with being a soldier, protecting the family, being chivalrous, etc.

The iconic man became known as the family provider and iconic woman retreated to her ‘private sphere’ as the caretaker, the nurturer.

This dynamic became the stock image for a 1950s family, but that does not work economically over time, McKinney said. Today, and even back then, most families were dual-earner families.

But when the manufacturing era ended around the 1970s, the idea of hypermasculinity developed. While there were still manufacturing jobs, the largest growing economic industry in the country became the service industry, which was considered women’s work.

For her social gender class, McKinney’s definition of hypermasculinity is simply the exaggeration of masculinity, emphasizing men’s physical strength, aggression and sexuality.

With their “manly” jobs on the decline, “Men have to find other ways to kind of live out their masculinity,” McKinney said.

Sports, for example, were not a big business until the late 60s and early 70s, when men tried to find other ways to be traditionally masculine.

By the 80s and 90s, masculinity became less associated with work and overlapped with other aspects of life. This was also around the time when there was a significant anti-feminist backlash, because the culture was changing and people did not know what to do about it.

Hypermasculinity was and is a response to changing gender roles across the culture, which is why it is exaggerated, McKinney explained.

Some of the greatest fears of men, Senior Karey Whitney described, were being seen as inferior to others physically, emotionally and verbally. So men exaggerate their masculine behaviors to be considered “more of a man.”

“The lack of emotional intelligence and encouragement to be a strong leader really creates an individual conflict that is promoted through an attempt at acting or trying to be something more than what you really are,” he said.

According to Whitney, every man has two faces. One is the one they show around other men and in public settings, and the other is the one they show to those who are closest to them.

According to McKinney, “Because men are more powerful in some ways, because the culture gives them more power, sometimes we fail to realize that our ideas of masculinity are hard on them.”