By Lauren Giese–Features Editor and Rayne Heath–Staff Reporter

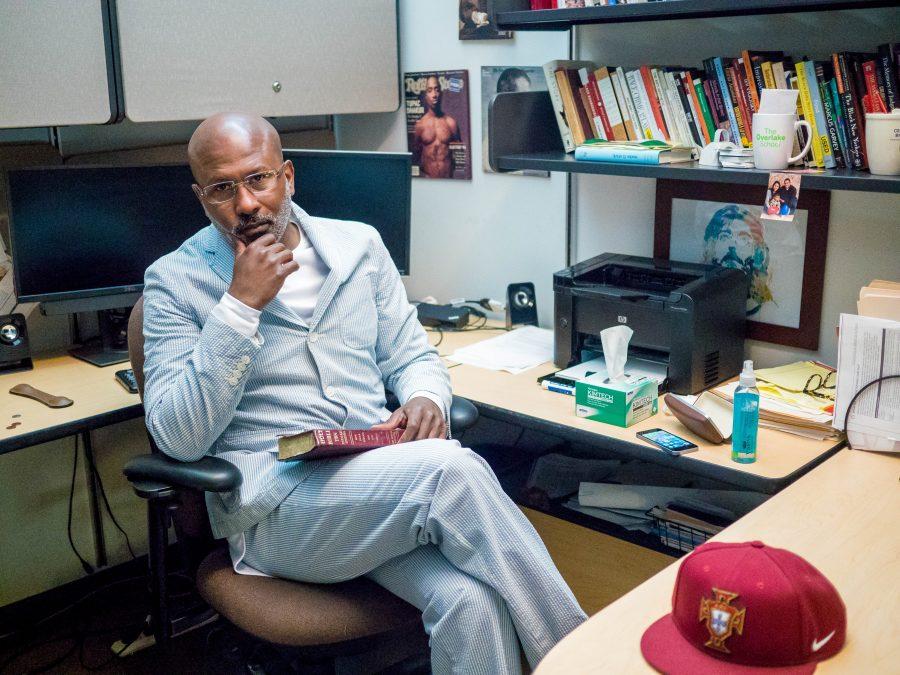

Tucked away on the third floor of Eaton Hall, a large banner stretches from the ceiling, bearing the logo of Harvard University; a bookcase filled with information on the sciences of medicine, bioethics and educational leadership lines the wall.

Scattered pictures tell the story of the life of Max Hunter, and testify of the loved ones that have helped bring him to this point. Many, including himself, would never have imagined that he would end up at Seattle Pacific University.

Hunter attended what he described as one of the “mega-schools” in the Los Angeles area. The average English literacy rate at his primary school was 27 percent, and he was no exception to this number.

“It was a struggle throughout school just because I started with this foundation of illiteracy,” Hunter said.

In the third grade, he moved back to San Diego to live with his grandmother, who he says is one of the greatest inspirations in his life. She worked day and night to send him to private school and provide him with the educational foundation he would need.

As a youth, Hunter worked alongside her as a janitor to help pay the bills until she fell ill and could no longer work. At that point, Hunter transitioned to the public schools.

“That’s when bussing really first started — It was the movement to desegregate schools,” Hunter said.

As a young black man, Hunter could still recall the feeling. “It was just a great experience, but the problem was that these schools were some 35 miles away from my home.”

This proved difficult for him to become involved in any kind of extracurricular activities, as he was limited by the bussing schedule.

Even with this, Hunter went on to graduate from his high school at the age of 17 and moved forward with the ambition to continue his education at San Diego State University.

While at college, however, Hunter seemed to find himself with more questions than answers regarding issues of philosophy, biology and matters of the faith. In an effort to understand, he sought the advice of a local priest.

Rather than providing Hunter with answers, the priest weakly attempted to offer words of comfort for Hunter’s troubled mind.

“I can still remember the day I left that parish. And when I walked out the doors I thought, ‘Well if he isn’t convinced or certain about the things of faith, then who knows?’ … And so I began to eventually live as though there was no God,” Hunter said.

Hunter dropped out of school, became addicted to the party scene, and was introduced to the drug trade by a neighbor. He soon began trafficking drugs between the East and West coast and figured that this lifestyle could propel him from the ghetto into the middle class.

Despite his choices, Hunter’s conscience gnawed at him throughout this stage in his life. He turned towards alcohol and cocaine to numb the pain.

“Even though I was pursuing a life of pleasure it left me feeling increasingly empty. There are narratives in our culture that tell you that when you acquire a lot of money, resources and status, that people will respect you and honor you.”

“There was some of that, but I didn’t feel like a respectable person. I knew that I wanted to be a person who was contributing to society in a meaningful and legal way,” Hunter said.

On the night of June 28, 1988, Hunter committed his life to Christ. “I was in desperate need of God and I repented and got down on my knees. I’ll never forget it,” he said.

In a matter of days, Hunter moved to Seattle for a fresh start. There, he earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Washington in comparative history of ideas and history of science, and began taking strides towards a new, redeemed life.

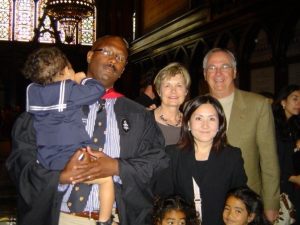

Hunter went on to study at Harvard University, where he took a certificate in Bioethics from the Harvard Medical School and was on its first community ethics committee. There, he was stimulated intellectually, but noticed a spiritual disconnect.

“It was like, ‘Leave your family outside the gates, leave your faith outside the gates, leave who you are outside the gates, just bring your brain,’” he explained.

Hunter carried this experience with him and considered the ways that he could stimulate growth in his own students in areas greater than intellect alone.

In 2008, Hunter found his way to SPU, largely due to the influence of Barbara and Gary Ames. Mr. Ames shared his vision to help African-Americans develop in their leadership, and Hunter began working with the John Perkins Center not long after.

“They kind of adopted my wife and I. They continue to be very supportive of our family and our children,” Hunter said.

As director of bioethics and humanities, assistant professor of biology, and director of pre-professional health sciences at SPU, Hunter strives to incorporate what Harvard could not into his teaching and student relationships.

“I think of education in holistic terms, so it’s not just my student’s minds, or the knowledge they acquire, or the skills they have. … Along with their intellectual formation, [education is also] their moral and spiritual formation.”

Today, Hunter incorporates his faith into his teaching and serves as a mentor for many of his students. He willingly meets with students who are seeking discipleship or guidance in their faith journeys.

Despite his achievements, Hunter remains humble, believing that one’s professional work should focus not on the self.

“It’s not about us, it’s never about us. It’s about the people we serve.”

Hunter describes this feeling as coming to appreciate the “acquired taste of the humble pie that God offers through service.”

“I find fulfillment in service. In this little institution, serving with my students, praying with my students, loving my family, trying as hard as I can to be a man of integrity, a Christian man — imperfect, flawed, but still striving — I am fulfilled.”

Reflecting on his life, Hunter sees the ways that God has changed him.

“When the God of all creation enters into a person’s life, if it’s not transformative, then the God of all creation didn’t enter into that person’s life,” he said.

“So when you enter into the lives of other people and institutions, it should also be transformative.”

As an instructor, Hunter believes he has a special opportunity to pour into the lives of the next generation, just as his grandmother did for him.

“I may not make a huge impact, but I hope that — and already believe that I have — impacted the lives of people who are going to change the world.”