In the midst of the uphill battle that was winter quarter 2019, a familiar and unwelcome email arrived from Nate Mouttet, the vice president for enrollment management and marketing at Seattle Pacific University.

As he did in 2018, Mouttet reminded SPU students that living and learning are by no means free.

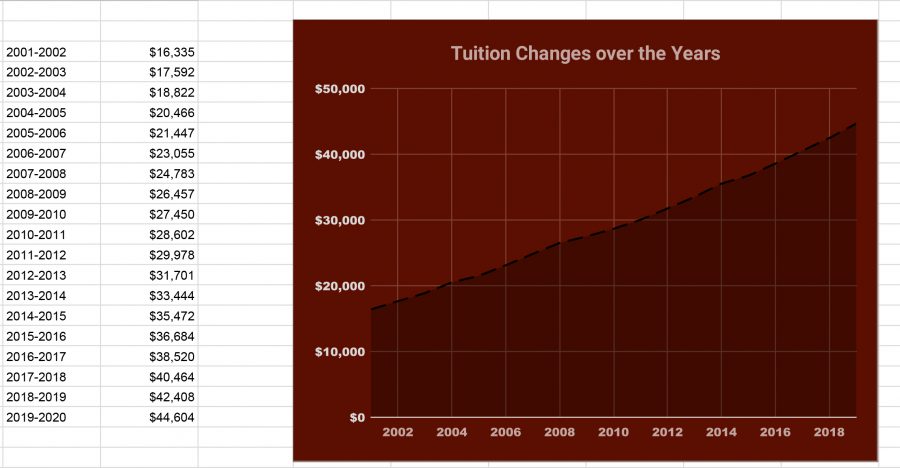

For the 2019-2020 school year, total fees will come to a whopping $57,363. The cost of tuition will be $44,604, room and board (assuming that a student has a standard residence hall double room and the Weekly 21 Block meal plan) will be $12,285.

According to Mouttet’s email, these fees represent a 4.8% increase from this current school year’s costs.

But where does the money go? Why should a year of college be more expensive than three 2019 Ford Fiestas?

These are the questions that came to mind this quarter as one of my former professors is being dismissed due to budget cuts, as my current professor informed the class that they are leaving voluntarily, and as the lights on Wallace field shut off abruptly during the second half of my intramural soccer game.

These are the questions that come to mind as I watch landscapers beautify the flora around the relatively opulent home of Dr. Dan Martin.

Although I do not have access to SPU’s complete budget (though I would love to see how much is spent on grass growing), we should consider how much SPU allocates to the highest paid university employees.

I examined an “executive-compensation” report published by the Chronicle of Higher Education in December 2018 which includes “the latest data on more than 1,400 chief executives at more than 600 private colleges from 2008-16 and nearly 250 public universities and systems from 2010-17.”

According to the report, Martin, the current president of SPU, made a grand total of $527,544 in 2016: 14 times more than the cost of tuition in 2016 and six times more than the salary of faculty member.

Considering that Martin’s pay increased approximately $23,000 from 2015 to 2016, it would seem accurate to estimate that, annually, our current president most likely makes a little under $600,000.

To put this into perspective, the base pay of the U.S. President is only $400,000 (not including other accounts, allowances, and perks of the position).

Other notable payments (for 2016) include the income of Jeffrey Van Duzer, the current provost who is set to resign, per the request of Martin, at the end of this academic year, who made $306,011, and Donald Mortenson, the then senior vice president of planning and administration, who earned $318,962.

But what do these numbers signify? How should we feel about the SPU president making more than a half million dollars as students struggle to pay exorbitant tuition prices, eating Top Ramen and Pop-Tarts while waiting for Friday payday?

Before answering, it is important to clarify that Martin is a valuable contributor to SPU. He performs administrative tasks that allow school operations to run smoothly and is the face of the school.

Second, this article is not intended on singling out Martin — he is paid a large amount by SPU because it is in their best interest to retain a qualified employee. The board of trustees shows how much they value Martin by how much they pay him.

But still, the fact of the matter is that while an increasingly massive economic burden is placed on the students and parents, SPU executives live comfortably and “Dr. Dan,” as Martin is affectionately known, lives in relative splendor in a house provided by SPU.

Although we are told that we, the students, are valued above all else, higher education isn’t measured in As and Bs. In reality it is measured in dollars and cents.

Board members must dedicate themselves to keeping college attendance more affordable. Even if that means paying themselves less.

If SPU wants to be an inclusive environment and maintain the ideal of higher education as a right for every student, regardless of socioeconomic status, it must be clear that students are valued. But it is hard to feel valued when the administration doesn’t seem to understand the lives of students it serves.

My life includes going to class and trying to put in enough hours to pay bills, tuition and food. Often I finish work at 12:30 a.m. and bus back to my apartment to finish homework.

As I work to pay for school, as U.S. student debt surpass the $1 trillion mark, and as the cost of attending SPU rises every year, I am stuck with two questions: “Does SPU want my mind or does it want my money?”