How patriarchy suppressed Ancient Egyptian queens

If one were to walk into Gwinn Commons and loudly propose the question “Who runs the world?” to the students therein, one would probably receive a resounding and unanimous reply: “Girls.”

Whether or not these Beyonce lyrics are true today, Egyptologist Dr. Kara Cooney would argue that they can be applied to multiple periods throughout the history of ancient Egypt.

On Sunday, Jan. 13, Cooney gave a lecture to a full auditorium as part of the 2019 season of “National Geographic Live,” currently being hosted at Benaroya Hall in downtown Seattle. The title of her presentation was “When Women Ruled the World,” which is also the title of her latest book that was published in October.

Unfortunately, in her lecture as well in her other published works, Cooney’s conclusions were not as auspicious — or feminist — as one might guess. Instead, Cooney explained that the power of women in history has been lost under the pervasion of patriarchy. “The story of female power in ancient Egypt is a tragedy.”

“Ancient Egypt allowed more females into power in the ancient world than any other place on Earth. Was that society somehow more progressive than we might expect? The answer is a quick and deflating no,” wrote Cooney in an article for Time magazine.

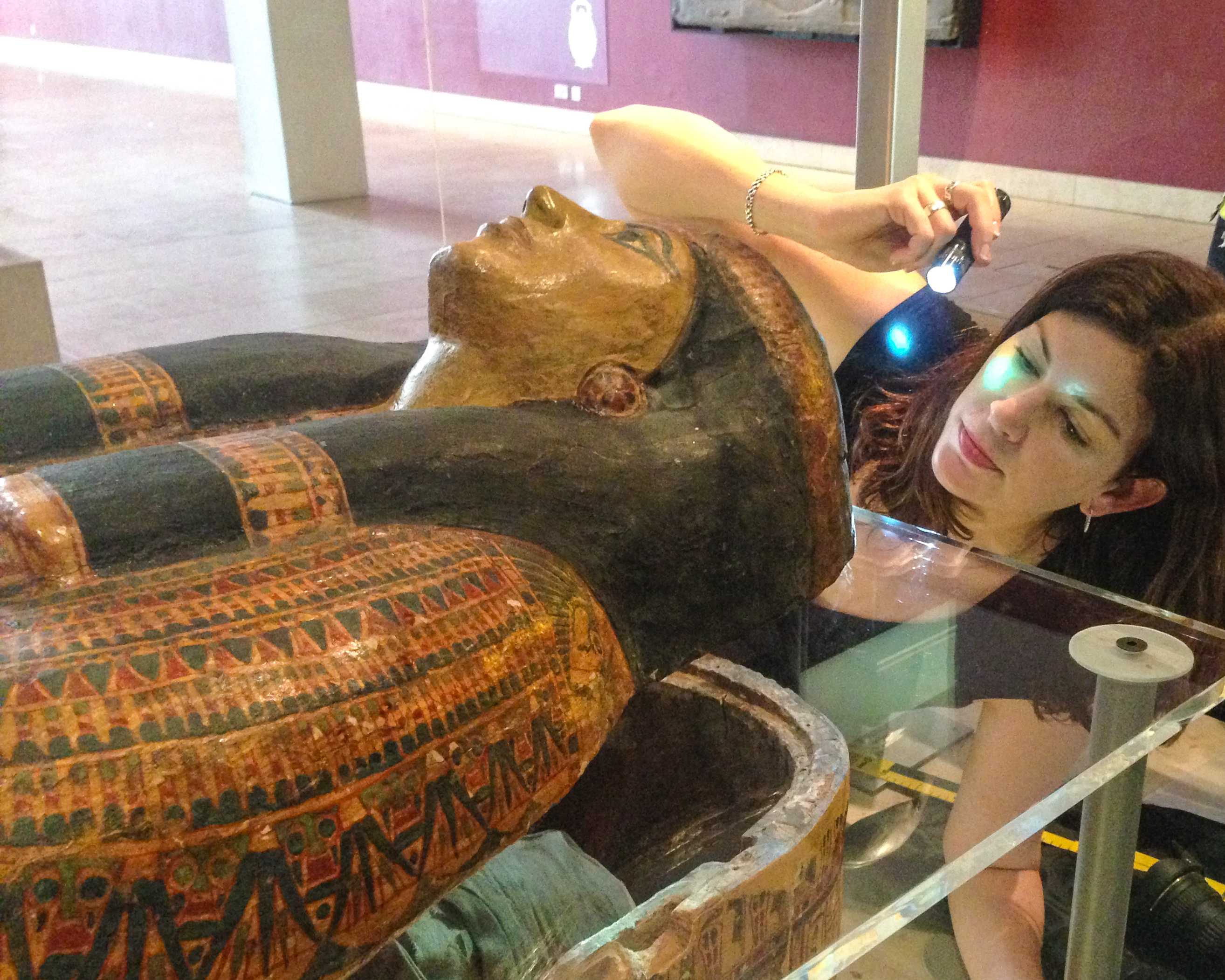

As an Egyptologist, professor of Egyptian Art and Architecture at UCLA, author and self-asserted “coffin-expert,” Cooney has spent years researching the ancient culture that has enchanted historians, archeologists, and film fans for ages.

Becoming interested in the prevalence of “female kings” (Cooney rarely uses the word “queens” as the contemporary connotation referred to a “mere sexual helpmate”), Cooney excavated the lives of six female pharaohs from the well-known, male-dominated history of ancient Egypt.

Through these women, Cooney recognized a trend that she proposes still exists today and is past its expiration-date.

Cooney found that, while more women in positions of power is often interpreted as a sign of progress, “history shows that what matters is not how many women rise to that level but what they do once they get there.”

That is, even though the pharaohs that Cooney studied held significant political, economic, religious and social power, they occupied their positions as place-holders. Their sole job was to “pave the path for the next male in line” by continuing the reign of their respective royal bloodlines and therefore protecting the patriarchal order.

“Six powerful queens, five of them becoming pharaohs in their own rights — and yet each and every one of them had to fit the patriarchal systems of power around them, rather than fashioning something new,” writes Cooney.

This does not mean that these women did not attempt to break the status quo.

Indeed, such pharaohs as Tawosret of Dynasty 19 and the famous Cleopatra of the Ptolemaic Dynasty wielded their power with unabashed ambition and unapologetic femininity. However, they both paid the price, ultimately relinquishing their reign by way of violent, male, force.

Tawosret’s rule came to a premature end, for example, when a warlord overthrew her in the name of “restoring law and order.”

As for Cleopatra, her death has been widely attributed to suicide. However, Cooney theorizes that this suicide might be a “convenient” story popularized by Octavian, her political opponent and proposed murderer.

Cooney posits that, no matter the means to her death, the greatest injustice done to Cleopatra is the dramatization of her failures which have effectively overshadowed her triumphs.

Even for those that accepted their roles as temporary rulers until the true successor came of age, injustice was dealt to them when their legacies were either reappropriated by a male king or erased completely from official records.

This practice, according to Cooney, has repeated throughout history and still persists today.

Citing Ivanka Trump and Sarah Huckabee Sanders as contemporary examples, Cooney explains how female power is often disguised as empowerment when in reality it is “power derived from speaking on behalf of a man.”

Thus, when looking at power today, Cooney suggests that “we must ask whom these women are really serving.”

According to Cooney, the answer, although not always obvious, is almost always a man.

“That is the tragedy of female power that the Egyptian female kings whisper to us from the past.”

Cooney left her audience with a motivational call to action, suggesting that there is a valuable lesson hiding in the lost histories of pharaohs like Tawosret, Cleopatra and Nefertiti:

“It’s not always easy to tell the difference between merely working in a patriarchal system and those who have chosen not to advance causes that help other women, but it is critical that we try.”