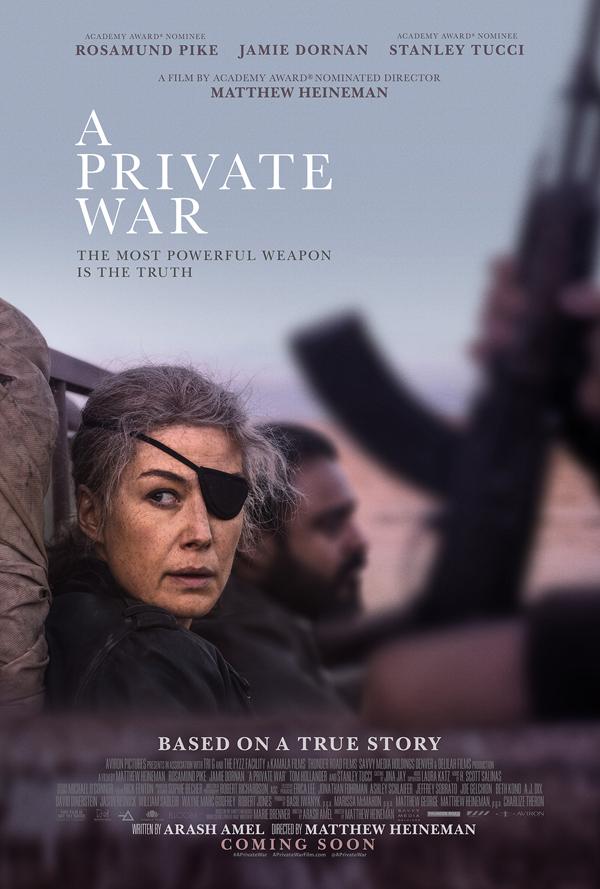

‘A Private War’ explores the complicated life of Colvin

Foreign War Correspondent Marie Colvin was killed in Homs, Syria in 2012, when the building she was in was bombed. Right before her passing, she had been telling the story of the suffering of citizens on live television through a transmitted interview.

Colvin’s life mission was to make people care about the people suffering in a world separate from her readers. She was willing to sacrifice her life to reach that goal. Colvin wanted to make the suffering of civilians trapped in areas of poverty and crisis real. In her words, “to make that suffering part of the record.”

The film “A Private War,” based on the Vanity Fair Profile of Colvin by Marie Brenner titled “Marie Colvin’s Private War,” follows the 10 years of Colvin’s life before she died.

Audiences accompany Colvin, played by Rosamund Pike, as she makes readers of the Sunday Times in London care about Sri Lankan rebel forces, Iraqi mass graves and Syrian civilian hospitals.

Driven by Pike’s powerful performance, Colvin is seen as complicated woman who has a hard time getting her bearings in any place that is not a war zone; all the while driven to manic episodes and flashbacks of the horrific suffering she had witnessed.

“You’ve seen more war than most soldiers,” Paul Conroy, a freelance photojournalist and friend of Colvin played by Jamie Dornan, said to Colvin in an attempt to make her understand the seriousness of her PTSD.

She is driven to alcoholism and smoking as a coping mechanisms for the images that relentlessly flash through her mind. In one scene, Colvin scrambles around her apartment amid a panic attack, desperately searching for a cigarette and a lighter to calm her racing mind.

All the while, her addiction is a constant reminder of her greatest fear: her own mortality.

“I fear growing old but I also fear dying young,” Colvin said in the film.

She throws herself into precarious situations to distract herself from everyone’s impending fate. Over time, audiences see Colvin change from someone who double checks if it is safe to run into an open field in Sri Lanka to running in front of gunfire to get where she feels she needs to be.

Colvin quite literally laughs in the face of danger.

Pike’s Colvin strives to be beautiful and modern.

She wears designer bras under her pragmatic work shirt and gets an eye patch instead of a glass eye. Yet she struggles to transition into the digital age as she almost accidentally deletes her story from her computer in a shelter in Iraq.

The film follows Colvin’s own internal battle as she is trapped between two worlds, that of a chaos overseas and her eerily calm life in London.

Pike and director Matthew Heineman make Colvin a complicated human being, not a token strong woman.

Jumping from warzone to warzone, details of the movie blur together just as they would in Colvin’s head. The shaky camera shots and natural sound increase the tension in each scene as the audience hears the heavy breathing of a character inside the film.

It puts audiences into the shoes of Colvin and makes them feel for her. Whether she is getting drunk at an awards ceremony, diving away from falling debris or watching the death of a child in a Syrian hospital, you cannot help but connect with her.

Both Pike and the makers of “A Private War” make audiences care about Colvin and care about the world she cared about.

She risked her life so people would know what is going on outside of their realities and she made it happen. She moved the abstract into the visceral by telling the stories of individuals citizens’ pain.

As Colvin said in an interview before she died, “I wanted to write something that would make someone else care as much as I did at the time.”

“A Private War” was released in theaters on Nov. 8.