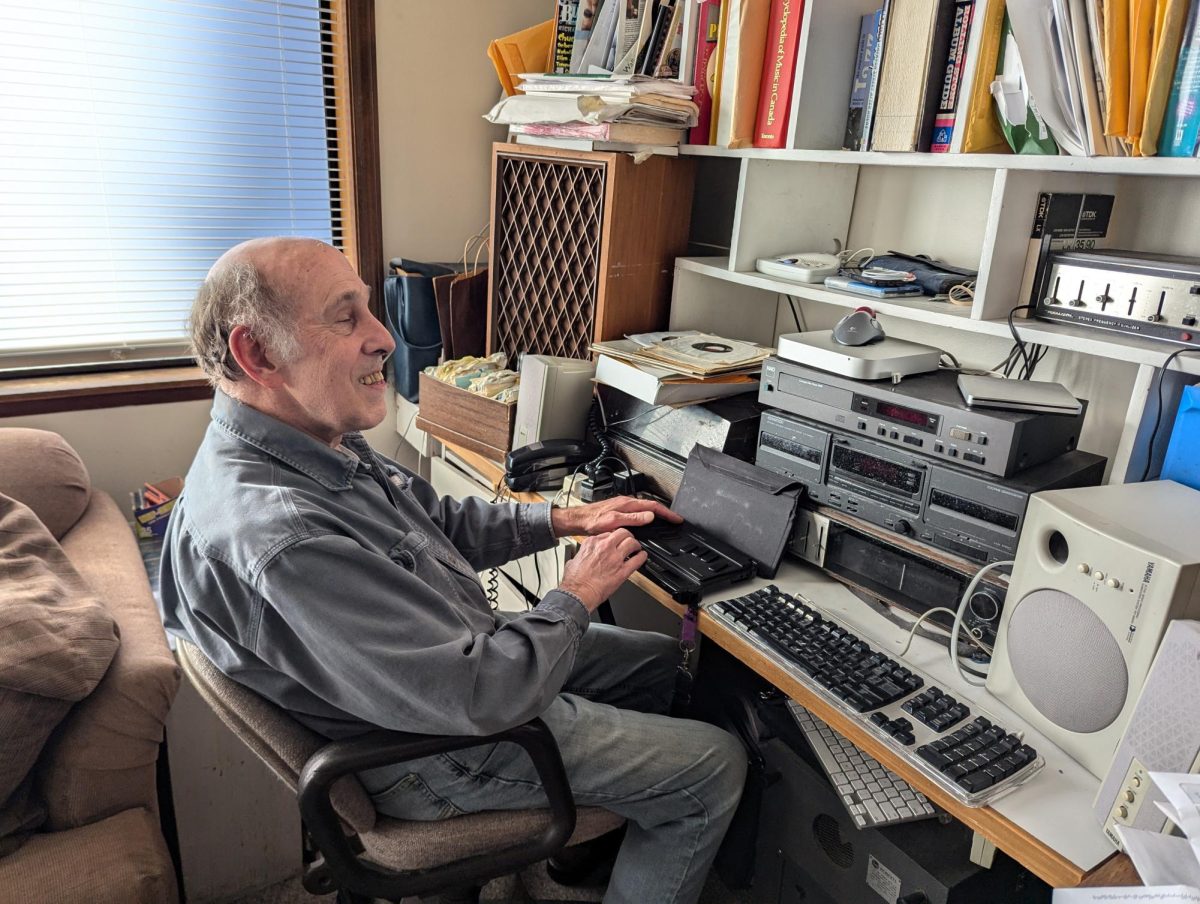

With shelves filled to the brim with music and files, a desk littered with audio equipment and keyboards, and a braille copy of The New York Times laid upon the dining room table—the apartment of journalist, musician and self proclaimed “capitalist pig” Doug Bright radiates a passion for the arts.

Bright, 74, lost his vision shortly after his premature birth when hospital staff filled his incubator with too much oxygen. Without his vision, he became deeply invested in music, specifically in the folk music that was rapidly gaining relevance in the 60s.

Bright has dedicated his life to performing and reporting on the music that he believes defined American culture through his publication Heritage Music Review, the headquarters of which also happens to be his apartment. He is jolly, consistently laughing and poking fun at the absurdity found in parts of his life. But driving that joviality and humor is a distinct sense of passion for his work.

“I’m probably the only person you’ve met all year who has a personal mission statement,” Bright said. “It says, ‘I am here on this Earth to enrich the world by preserving the music and philosophy that made America great.’ Now, that’s a reason to get up in the morning.”

His interest in journalism first started when Bright was a teenager after going to a performance of folk icons The Brother Four, Josh White and Ian & Slyvia with a friend.

“His mom read us a review the next morning, and it was the stupidest thing,” Bright said. “It was obvious that whoever wrote that article didn’t know diddly squat about folk music and I thought, even at the age of 15 or 16, I could have written a better review.”

Nearly two decades later, after dropping out of college, getting married, gaining some freelance journalism experience and establishing himself as a professional musician, Bright began brainstorming ideas for his own publication. The answer lied not in his brainstorming, but in his dreams.

“One night, I had a dream,” Bright said. “I just kinda woke up that morning and I decided it was gonna be all about music, it was gonna come out once a month and it would have a performance calendar. I know for a fact if I hadn’t written that inspiration down, there would be no Heritage Music Review today.”

42 years later, Bright is still dedicated to monthly editions of his paper. Walking into a Seattle guitar shop like Dusty Strings or Emerald City Guitars, customers are greeted by copies of Heritage Music Review for sale. The eight page yellow booklet paper is exactly what Bright envisioned in 1981. Thanks to Bright’s friend, Karen Holt, he is not directly involved with the page layout process. For $1.25 an issue, or completely free online, anyone can read various articles and a list of concerts written and cultivated by Bright. His goal is, and always has been, to highlight the genres of music he feels made America great, so he makes sure to vet the couple dozen acts he promotes in each issue.

“Everything that’s on that calendar, to the best of my knowledge, is a personal recommendation,” Bright said. “I’ve either heard them live or I’ve checked them out on the web.”

Assistive technology meant to aid the blind has developed right alongside Heritage Music Review, ultimately making the process easier every year. While an early ‘80s machine capable of encoding braille text onto a cassette tape once left Bright feeling like “the king of cyberspace,” devices that allow him to interact with the internet have changed Bright’s life. When Bright first began Heritage Music review, we would take notes on a braille slate by using a stylus to punch out dots in a paper. He would then transfer that to a braille typewriter and eventually to a standard typewriter to be physically cut and pasted onto a page. Now, Bright can just type directly into his braille tablet and upload it to his website.

A jam buddy of Bright’s, Bradford Hull, helped make his website more easily accessible. Bright met Bradford at a jam, after taking notice of his involvement with technology.

“He noticed that I was likely to be playing with a computer when I wasn’t playing with a bass,” Hull said. “He just asked me if I could help him with his website and I asked took a look at it and said ‘I don’t have a huge ton of skill, but I think between the two of us we might be able to work out a way for you to be able to maintain your website without anybody else being involved.’”

Hull did exactly that, automating more parts of the website to ensure Bright needed less help. Hull ran one of the internet’s largest quote compilation websites of the early internet, so the upgrade did not come as a particular struggle to him.

Writing and editing a small paper every month is a timely ordeal, even with assistive technologies, but he is dedicated to putting out an issue each month.

“I have really given myself an uphill task,” Bright said.“I am really doing things the hard way but hey, this is my life’s work. It’s just gotta be done.”

Bright still works as a musician, performing in groups of multiple genres including Louisiana oriental, folk and vintage jazz. Bright finds himself performing everywhere from parks to old folks homes, playing the music that is special to him. His musical experience gives him a greater insight into the venues and types of music he reports on.

Bright’s work with Heritage Music Review goes largely unnoticed by the average citizen of Seattle. With the paper only being carried at less than a dozen shops, and the dwindling amount of people actively searching for folk and jazz shows, its lack of prevalence is not exactly surprising. But while Bright’s life work may be most commonly viewed in passing at guitar shops and bookstores, its reach is not what is important. Bright’s work fills a very specific niche, and as long as he is filling that niche, he is doing what he feels he is meant to do.

“When my life works properly, it’s a really nice balance,” Bright said. “Writing and researching is quiet and solitary and intellectual. Performing is gregarious and ‘out there.’ When the two things work together, it’s a good life. I really think that if I got rid of either one of those, I’d burn out.”

The digital edition of Heritage Music Review can be found at www.heritagemusicreview.com.