In May 2022, Josh Anderson sat in the sanctuary of Mosaic Community Church and realized the place he had called home for almost two years would never accept who he was.

Mosaic Community Church opened in Seattle as part of the Antioch International Movement of Churches, an evangelical church-planting organization. Beginning in 2005 and for the following 14 years, Mosaic was nomadic, meeting in apartments, houses, concert venues and community centers. By 2021, Mosaic planted two additional churches in Washington — one in Edmonds, called Mosaic North, and another in Bellevue, also known as Mosaic Eastside. The original group, now named Mosaic Seattle, moved into a permanent location on Aurora Avenue in 2019. They currently welcome members, many of whom are college students, through their doors every Sunday.

Though Mosaic Seattle’s college group is made up of students from all over the city, a majority of them attend Seattle Pacific University.

Joining the church

As a freshman at SPU in the fall of 2020, Gloria Diehl was looking for a way to build community despite the COVID-19 restrictions on campus. She found that community at Mosaic, a non-denominational church.

“Something I was looking for in a church was one that had a lively college group,” Diehl said. “Mosaic was also one of the [churches] that was open in-person, and so it was helpful for me to get off-campus and meet people that way.”

Diehl quickly made friends at Mosaic, and within weeks of attending the church, a small group leader reached out and asked if she would like to be “discipled.”

“That’s like a one-on-one relationship where they ask, ‘How is your spiritual life?’” Diehl explained. “‘Have you talked to Jesus? What has Jesus been teaching you?’”

It did not take long for Diehl to become heavily involved at Mosaic, including going on a mission trip to the Dominican Republic the summer after her freshman year and becoming the college group’s worship leader six months later.

During her time with the church, Diehl was discipled by multiple women. One of her mentors was Hailey Echan, another SPU student two years older than her.

Echan joined Mosaic in 2018 and eventually went on to serve as an intern for the church after her graduation. Initially, Echan visited Mosaic with a friend who played on the worship team. This was after Mosaic purchased property on Aurora Avenue, but before renovations on their new building were complete.

“I fell in love with it,” Echan explained. “It felt like they were really people who loved God and loved people.”

On Mosaic Seattle’s website, their motto can be found in bold white letters: “Because Jesus loves us, we seek to love God, love people and change the world.” Echan reiterated this and other Mosaic-specific phrases over Zoom from her apartment in East Asia where she lives and works as a student.

Diehl was not the only SPU student looking for community amidst the pandemic. Anderson, too, joined Mosaic’s college group in 2020, a few months after Diehl. Similarly, Anderson quickly became involved with the church and the college ministry. Though he never filled a “spiritual” role like Diehl did, he was part of a team who helped plan and host events.

Anderson developed deep friendships with other SPU students who attended Mosaic, including five young men. The spring of his sophomore year, and only a short time before he left the church for good, Anderson signed a year-long lease to live with the friends he made at Mosaic.

Starting to question

After a year of involvement, both Diehl and Anderson started feeling uncertain about the church they had come to view as a home away from home. They became uncomfortable by the vagueness of Mosaic’s theology and the language used by church leaders.

“Mosaic teaches you not to trust yourself,” Anderson said, referencing the phrase often used to encourage Mosaic members: “God is honored by your ‘Yes.’”

Though the phrase may appear innocuous, Diehl felt incredibly harmed by its use. During her tenure as college worship leader, she experienced debilitating panic attacks.

“I would have panic attacks before I traveled to Mosaic and then once I was at Mosaic,” Diehl explained. “I would either have a panic attack before I led rehearsal or in between rehearsal and the service.”

Often, Mosaic’s church leaders would still ask her to lead worship that night, invoking the name of God to motivate her. They would say, “God is honored by your ‘Yes,’” implying to Diehl that if she said no, she was going against God.

Anderson and Diehl were beginning to question the church — and so were their peers. At SPU, Mosaic had developed a controversial reputation among the student body, a reputation that stemmed from multiple sources.

Jenna Osburn, a senior at SPU and a leader for one of Mosaic’s house churches, has observed that the worship style at Mosaic makes some newcomers uncomfortable.

“Mosaic is a bit more spirit-led in that way,” Osburn said.

Members at Mosaic often jump and dance during the musical portion of the service, and some even fall to their knees in tears or cry out in exaltation. In many other Christian denominations and churches, worship appears more reserved.

“I think [for] some people, it’s like way out of their comfort zone, and they haven’t experienced it,” Osburn explained.

Alternatively, Echan saw that many of her peers disliked Mosaic’s stance on LGBTQ+ issues.

“From my perspective, and from a lot of people’s perspective, that’s the one thing people don’t love about Mosaic,” she said. “That was the big controversy with Mosaic, and I think it still is.”

On the “Beliefs” page of Mosaic’s website, they include an appendix document that lays out their doctrine concerning sexuality. This document was only added to their site in November 2022; it was not public at the time Anderson and Diehl joined the church.

“Regarding the topic of homosexuality, Antioch has consistently upheld a stance of clarity and

compassion,” the document reads. “Clarity that the practice of homosexuality is sinful, and compassion toward those who sin sexually, experience sexual confusion or deal with unwanted sexual desires.”

Echan also emphasized Mosaic’s doctrine, saying “[homosexuality] is just like an attack on the human race to pull them farther from what God intended people to be.”

When asked for additional comment on their ideology, Mosaic leadership provided a link to their “Beliefs” webpage.

Diehl experienced real side-effects of Mosaic’s reputation in the fall of her second year at SPU, after a mix-up with housing caused her to move dorm floors. She discovered that her new Resident Advisor was wary because of her association with Mosaic.

“I found out that she was nervous for me to move on to her floor because she knew I went to Mosaic, and that was kind of a moment where I was like ‘Crap. People shouldn’t be afraid of me because of my faith.’ Like that’s never, ever a good sign,” Diehl said.

Non-affirming in Seattle

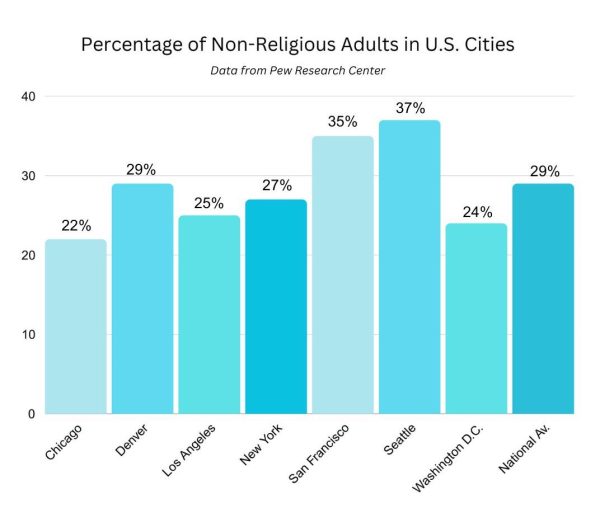

Seattle is notorious for being a city without religion. According to the Pew Research Center, 37% of adults in Seattle are not affiliated with any religion, compared to 29% nationally. Seattle is also well known for being gay; almost 11% of Seattle residents identify with the LGBTQ+ community, compared to 7.6% nationally.

As a result of this unique culture, many Seattle churches are affirming of homosexuality — Mosaic is not.

When referring to Christian churches’ beliefs about LGBTQ+ issues, there tends to be two descriptors used: affirming and non-affirming. “Affirming” refers to churches that accept and celebrate their LGBTQ+ members’ identities. “Non-affirming” describes churches that do not.

Echan stated that Mosaic is a non-affirming church, which is unusual in one of the gayest cities in America.

“It’s so opposite to, I think, what most churches in Seattle stand for now,” she said.

Mosaic’s non-affirming stance is one-of-a-kind in Seattle, but their countercultural mindset puts them on a long list of conservative, American churches.

“Mosaic was not born uniquely,” Anderson said. “[It] is a product of American Christianity. It is fiercely individualistic. It is fiercely experiential.”

On the outside, Mosaic appears to be different from more traditional churches. Anderson described the atmosphere of Mosaic: Edison bulbs hanging from the ceiling, minimalist white walls, “cool” concrete floors and sparkling water on tap.

“It’s a very particular flavor,” he explained. “The thing that is said repeatedly is ‘It’s not a denomination, it’s a movement.’ It fits the countercultural mold of Mosaic to be like, ‘We’re not a denomination,’ or ‘We’re not your grandpa’s church.’ But it’s not unique. It’s a product of a highly emotionally-manipulative and emotionally-reactive-based spirituality.”

The night that changed everything

In the spring of 2022, SPU erupted into chaos. After years of protest in response to the school’s employment policy, which forbids the hiring of LGBTQ+ faculty, SPU’s student body had had enough. On May 24, 2022, SPU students began a sit-in outside the administrative offices, demanding that the board of trustees change their policies or face a lawsuit. The sit-in lasted almost two months.

For Diehl and Anderson, who both identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community, the SPU protests were the catalyst to their departure from Mosaic.

Diehl was among the students who participated in the demonstration. Anderson was not.

“I was deeply ashamed,” Anderson said of his abstention. “People knew me as part of the Mosaic crew, and if I went to the sit-in, I knew that there would be sins I had to answer for. I think that there was a lot of shame in the fact that those people were protesting for me, and I didn’t help my community, my people.”

Mosaic’s college ministry decided to respond to the SPU protests at their monthly college night, the final one before summer break. The college group leaders invited Andrew Franklin, the pastor of Seattle Eastside, to speak — Franklin is a self-proclaimed ex-gay man who is married to a woman, with whom he has four children.

“The point of the night I think was to open a conversation and just talk about it,” Echan said, “it” being the conflict at SPU. “Because Mosaic had been blamed in the past for just ignoring it and not talking about it and not making a space for students to really process things.”

Unfortunately, the night did not play out the way Echan hoped. Though she was not involved in planning the event, she was one of the students who introduced Franklin and kicked off what was meant to be a question-and-answer session.

“I think it kind of came across, because of the timing and because of the topic and because of the way [Franklin] approached it, it came off as basically, like we’re telling everyone that students at SPU are wrong for [protesting],” Echan said.

Mosaic leadership intended for Franklin to answer student questions and participate in conversation with them. Due to a miscommunication, the structure of the sermon became a monologue, rather than a back-and-forth exchange.

That May night was the moment Anderson and Diehl knew they needed to leave Mosaic.

“I was already thinking about maybe leaving, and that night just kind of gave me closure that it wasn’t the place for me to continue exploring my spirituality,” Diehl said. “It was, for me, harmful, and I didn’t feel like it was a safe place.”

In his sermon, Franklin discussed God’s design for humanity, and stated that “God had a better way” for LGBTQ+ people — meaning they should ignore their homosexual attraction and instead live a heterosexual life. This sentiment angered Anderson, who had recently come out to a handful of friends at Mosaic.

“So, God’s design is for me to feel so isolated, even after I’ve shared openly and vulnerably with my brothers and sisters in Christ, about how ostracized I feel for not being heterosexual in this world?” Anderson asked. “God’s will is for me to always feel like an outcast, always be unwelcome, to be the butt of jokes in my all-male Bible study groups, to have to always educate, to have to always assert my own dignity? I want no part of that.”

Franklin’s sermon spread, as rumors do, across SPU’s campus. Mosaic’s already shaky reputation became worse.

Little did that year’s student body know they were not the first round of students to cast Mosaic aside. Mosaic Seattle had experienced a mass exodus of members years earlier in 2016, due to their beliefs about homosexuality.

Not the first time

In 2018, one of Echan’s friends, who she had gone to Mosaic with for many months, left the church because of her identification with the LGBTQ+ community. After seeing her friend leave Mosaic, Echan felt she needed to solidify her personal doctrines. She approached the church leaders to ask questions of Mosaic and her own beliefs.

At this time, Echan was told about the 2016 incident by one of her mentors. Echan referred to the event as a “giant purge.”

“It wasn’t because of anything Mosaic did, it was just more of people realizing what Mosaic believes and then just leaving,” Echan said of the mass exodus.

Tait Weicht, an SPU alum, attended Mosaic from late 2016 to early 2020. Though he had not yet come to Seattle when the exodus occurred, he heard stories secondhand from his peers.

“I heard people telling me, ’Oh, there was a purge, where they came down really hard,’” Weicht explained.

In 2016, there were a number of LGBTQ+ members of the church who questioned Mosaic’s beliefs. When Mosaic clarified their non-affirming stance on LGBTQ+ issues, many people condemned the church and left, never to return.

‘They’re not talking about me’

Weicht, a gay man, “came out” to himself during his sophomore year of college, though he only told a handful of people at the church. He was aware of Mosaic’s beliefs about homosexuality for almost his entire tenure at Mosaic, but always managed to convince himself that he was the exception.

“I’d say, ‘They’re not talking about me’ or ‘It’s not an indictment on my behavior or anything,’” Weicht explained.

Additionally, Weicht thought he could help Mosaic change to become more inclusive. He tried to share queer theory and theology with his peers and mentors, and even suggested to a friend that they start an LGBTQ+ Bible study at Mosaic. In each conversation, he was instantly shut down.

Jennifer McKinney is a professor of sociology at SPU who studies gender, family and religion. She explained that what Weicht experienced is not uncommon. For evangelical groups, particularly churches with strict heterosexual family values, there is very little room for discussion.

“Each individual church thinks that they have a line on the truth,” McKinney said. “You have relationship with these people, these are the folks who are your disciplers and mentors, and suddenly you’re trying to engage them, and they are having none of that, because to them it’s better to sunder the relationship if you refuse to believe their line.”

In the late 2010s, several Mosaic students came to McKinney with their stories, and she noticed an alarming trend among them.

“Prior to COVID, I regularly had Mosaic students show up in my office and we talked about gender and religion and there was an interesting pattern with people from Mosaic,” McKinney said. “Almost always they were sophomores, winter or spring quarter. They’d been at Mosaic their whole time at SPU. They were just now discovering how strict gender ideology and the anti-LGBTQ bias was.”

While these students, like Weicht, were somewhat aware of Mosaic’s beliefs, they managed to gloss over them. McKinney explained that this oversight can be a result of an evangelical upbringing. Students who are raised in non-affirming churches may see these issues as “the furniture” of their religious life — always there, yet easily overlooked.

“A lot of the stuff is invisible until you’ve been taking classes at SPU, until you’re living with people who are LGBTQ-friendly and are part of the LGBTQ community, and you start to see things a little bit differently,” McKinney said.

McKinney has also witnessed how students are often unable to bring their concerns about LGBTQ+ topics to Mosaic leadership.

“A lot of the students I have talked to did not want to end their relationship [with Mosaic],” McKinney said. “They felt like they could be salt and light into the church to help them understand, but then they were being shut down.”

Anderson, too, was aware of Mosaic’s beliefs about homosexuality only a few months into his time there. Still, he kept coming back, and he saw other LGBTQ+ students do the same.

“The people are already plugged in, and this is their community. It’s easier to stay,” Anderson said.

Growing up evangelical, Anderson has seen, and felt, the harm Christianity can cause. Undoubtedly, Mosaic is not the only church to have enacted pain on members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Yet, being Christian and being gay are not mutually exclusive. Many LGBTQ+ individuals, including Diehl, still identify as Christian. Because of her time at Mosaic, Diehl experienced a lot of hurt — she also experienced a lot of growth.

“[What I went through] made me feel more confident in what my theology of Christianity is, and that it doesn’t align with [Mosaic’s], and that’s okay. And that can exist,” Diehl said.

Almost two years have passed since Anderson and Diehl left Mosaic Community Church. On the “College Ministry” page of Mosaic’s website, photos of Anderson can still be found.

Peter • May 27, 2024 at 8:27 pm

This article would be much better if it included Scripture to support the positions made. As is, it is rather one-sided. Both in its portrayal of the church and the Falcon’s position on TGBTQ issues.

Sydney • May 23, 2024 at 11:31 am

Aubrey is such an informed and well written journalist. I love the variety of perspective and elaboration throughout this entire article. I can instantly tell the time, care, and consideration that went into this article.

Jenna • May 23, 2024 at 8:09 am

A much needed and incredibly well written article!

Peter Thomson • May 22, 2024 at 3:41 pm

Thank you for this piece, though it is rather one-sided. It would be much better if you presented the Scriptural references for each position.

Natalie Roy • May 22, 2024 at 2:46 pm

Thank you for writing this. It needed to be brought into the light.