★★★★☆ (Four stars)

The film industry, by nature, is exploitative. Its foundation is built on– and is still stable today– because of overworked and underpaid employees whose recognition will rarely be publicly applauded. The film industry is exploiting me right now, spending my time writing what is essentially free promotional material because my position as a journalist has been framed on a reliance of the media. It is exploiting you right now as you read a review for a movie that whether you see it or not, is now alive in your consciousness, which could do nothing but help their business. The film industry certainly exploits Angela Raducani (Illinca Manolache) as she works long hours as a production assistant.

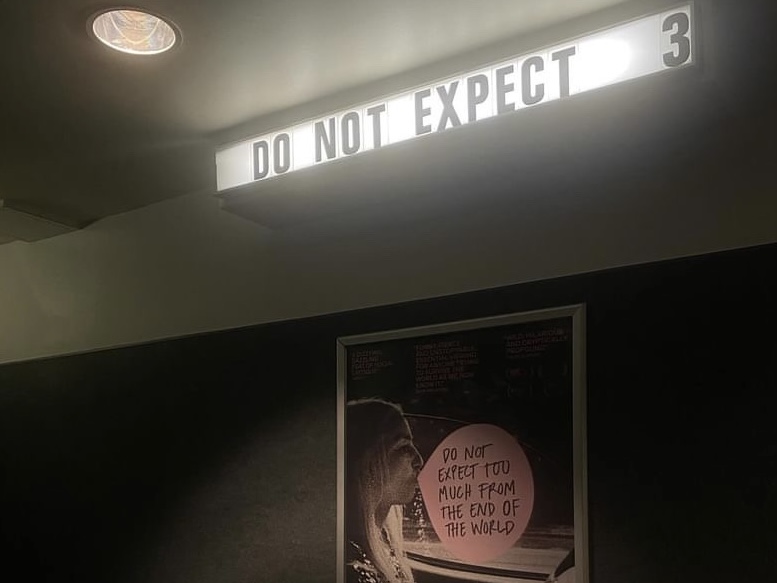

“Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World” is director Radu Jude’s first film following his Best Picture win at the 2021 Berlin International Film Festival for his other long titled “Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn.”

“Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World” was the masterful comeback everyone expected from a director who established his smart satirical and indulging proactive tone. The movie is a wickedly smart venture that explores corporate exploitation of the class divide, political resentment and the absurdly comical danger of social media’s influence.

To see this movie is to live in this movie — for the two-hour and 43-minute run time, you are immersed in the street life of Bucharest, Romania, or at least the life we see from the windows of Angela’s car. The story follows Angela, a product assistant working 20-hour days as she drives around “auditioning” citizens who have been injured on the job for a workplace safety video while taking moments throughout her day to build her online persona Bobita.

One of the first things we learn about Bobita (a poorly disguised Angela with a bushy eyebrow and bald filter) is that he is close friends with Andrew Tate. While this tells you almost everything you need to know about Bobita, what you come to realize is that Bobita acts as Angela’s release.

Dealing with an exhausting life in which she comes face to face with a fair share of misogynistic remarks, difficult coworkers and the grueling weight of helplessly managing the hope of many looking for a chance to tell their story, Bobita acts as the medium between her angst and real life.

Shot in high-contrast black and white 16mm film, each frame is breathtaking. Playing with natural lighting that compliments beauty in the ordinary while acknowledging the despair of the norm, this film is visually stunning. Often taking a documentarian approach, the camera angles are played with in a way that matches the emotional tonality of the film’s content. The movie feels personal, whether you can relate to it or not, and the approach feels conversational and draws in the audience.

This film did act as a response to the 1982 “Angela merge mai departe,” a film about a taxi driver in Bucharest navigating relationships. With intercut sequences comparing the two Angelas and their emotional landscape, the only bits of color we are privy to come from the pieces of the older film.

“Angela merge mai departe” was made under censorship at the end of Ceaușescu’s political rule; it shows what would be considered now as a very sanitized approach to the life of a taxi driver. Jude revisits the older film in his own as a way to draw on the stark contrast between art made under censorship and made with full artistic freedom. His take is one that is bleak, raw and incredibly vulnerable — it is what audiences would have liked to see represented over 40 years ago.

The lead of “Angela merge mai departe,” Dorina Lazar, reprises her role as the mother of the man chosen for the work safety video.

The performances of the ensemble cast, specifically those auditioning for the work-safety video, were so pure and raw that it would be easy to forget you are watching a scripted movie. Manoloche does a phenomenal job guiding this movie — it takes a strong lead performance to turn what could have been an uninteresting premise into a once-in-a-lifetime striking performance.

The film could easily– under false guise– be categorized as a “nothing happens” movie. However, in the quiet nothingness of a day-in-the-life format, you get a film packed with socio-political commentary. Though it may take more out of you than the average movie, if you spend time searching for it, you will find that the film is full of deep purpose. The final sequence, a 20-minute single shot, will stick with you and broaden the scope of what smart cinema can look like.

If you are willing to open yourself up to what Bong Joon-Ho calls the “one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles” and spend the time really thinking about what the film has to offer (not that it is hard, as the film demands to be heard) you will find yourself watching what I can confidently say will be one of the best movies of the year.