David Brooks brims with stories.

Those who heard his presentation in the First Free Methodist Church for Seattle Pacific University’s inaugural event on Thursday, April 11 included students, faculty, alumni, literati and members of the FFMC. The esteemed journalist was surrounded by a small crowd of admirers at all times, drawing whispers and pointing from those settled in the pews.

His most recent book “How To Know A Person” was promoted at SPU’s event. The first 100 students to show up with their school ID received a free copy and likely an autograph to fill its cover page.

At 3 p.m., professor Brian Lugioyo gave the opening prayer to a near-full chapel. This was followed by an introduction from President Deana Porterfield, who, after describing how the journalist and author writes for the New York Times and The Atlantic, commentates for PBS NewsHour and makes the New York Times Bestselling List with every book published, gestured to him.

“David,” Porterfield said, smiling. “Please come.”

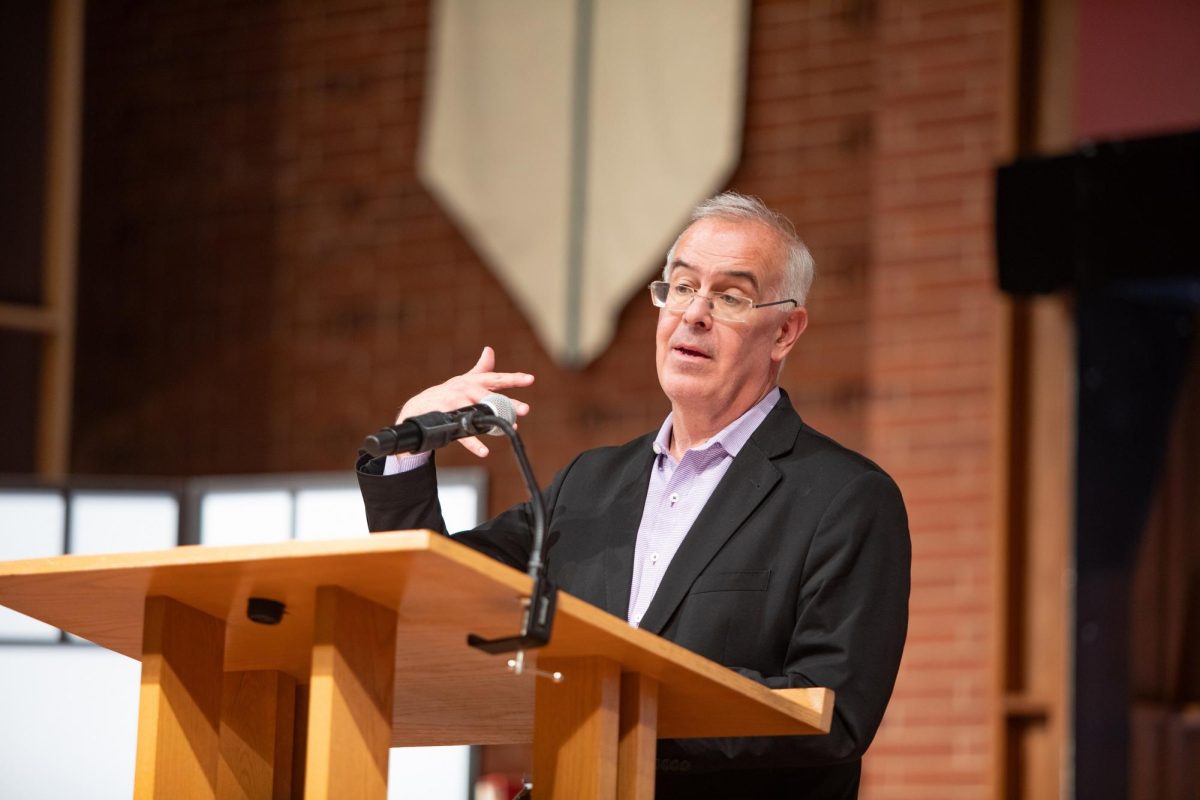

To thundering applause, Brooks took the podium and set about cracking jokes and telling stories about his “cerebral,” intellectual life — detailing how he came to connect with emotion and the people around him.

“Over the course of life, you get softened,” he said, later describing emotion and intimacy as the “holy sources of life itself.”

This softening characterizes Brooks’ point: in an age of depression, suicide and loneliness, we must build and treasure relationships like never before. Brooks sees sadness as a precursor to anger and hatred, listing increasing statistics of suicide, hate crimes and gun violence.

“We’ve become sadder, and when you become sadder, you become meaner,” Brooks said.

To combat this epidemic of hatred, Brooks recommends being curious about and building empathy for the people in a person’s life. He also recommends loads of literature, a splash of faith and real presence in relationships. Asking questions is an easy route to growing intimacy.

Brooks offers some examples: “Why do you believe what you do? How do your ancestors show up in your life? What would you do if you weren’t afraid?”

Rick Steele, professor emeritus of moral and historical theology, knew Brooks as a frequently-read journalist and author who “really had something to say.” When Brooks took the podium to begin his speech, Steele stood while applauding.

“The distance between concept and illustration is very short for him,” Steele said.

Steele focuses on personal relationships and emotional closeness in his life and teaching. Brooks’ ideas about these topics resonate deeply with him.

“The sequence of calamities that occurred in the world over the last 15, 20 years has in part to SPU, largely in our culture, made us angry, resentful, polarized,” Steele said. “It’s made us fixate on issues of policy, without getting to know each other individually.”

In the context of recent controversies at SPU about their LGBTQ+-exclusory hiring policy and the impactful budget and faculty cuts, Steele emphasizes that relationships come first.

“The priority here was the triangular relationship between one person, another person and Jesus, and that’s what we do, or what we used to do,” Steele said.

According to Brooks, hard conversations follow knowing a person, not the other way around.

Even with foundations of curiosity and love, disagreement arises. Political polarization is rampant, and the politically focused journalist unexpectedly says it is unimportant, at least not in relation to friendships, spirituality, and love.

“If you’re asking politics to fill the hole in your heart, you’re asking more of politics than it can do,” Brooks said.

To close his speech, Brooks told a story that reflected his simple, deep understanding of relationships. In the summer, Brooks sat reading in a room brimming with plants. His wife walked in and paused, not seeing him, just standing still and gazing at an orchid. Silhouetted by the sun, she was gently regarded by Brooks, who remembers thinking, “I really know her. I know her through and through. I was just beholding her.”

After another exciting round of applause, audience members could ask Brooks questions in a moderated discussion. Topics included conditional love, anti-Semitism, vocation, politics and Christianity. Brooks has an interesting perspective; ten years ago, he converted from Judaism to Christianity.

“From a Jewish perspective, Jesus is a total bada** that leads with humility,” Brooks said.

Since his conversion, Books has noticed less interest in politics, no change in morality and a deeper understanding of the world’s need for joy. He said, “Our deep gladness is the world’s deep need.”

Part of Brooks’ deep gladness is his affinity for and love of storytelling. He shared an experience about cold interviewing a volunteer woman after the fall of the Soviet Union — a woman who had grown up in the Palace of the Tsar. Living through the revolution, losing husbands to gulags and children to violence, everything bad that could have happened to her did, and Brooks still remembers and speaks of her.

“[Brooks] knows exactly how to take on a key idea,” Steele said. “You never feel like you’re trying to follow his argument because his arguments are the stories he uses all along the way.”

After a session filled with tales, jokes and quotes from figures like D.H. Lawrence and Victor Frankl, Brooks spoke to college-aged individuals like those in the audience. He described the four years of university as parentheses of contemplation and recommended doing three radically different things in a person’s 20s.

“Life will happen, and life is really short, and right now, you’ve got the freedom to ask big questions. Seventy percent of you at age 30 will be boring,” Brooks said, deadpan. “Don’t be that seventy percent.”

And, once more, applause for David Brooks.