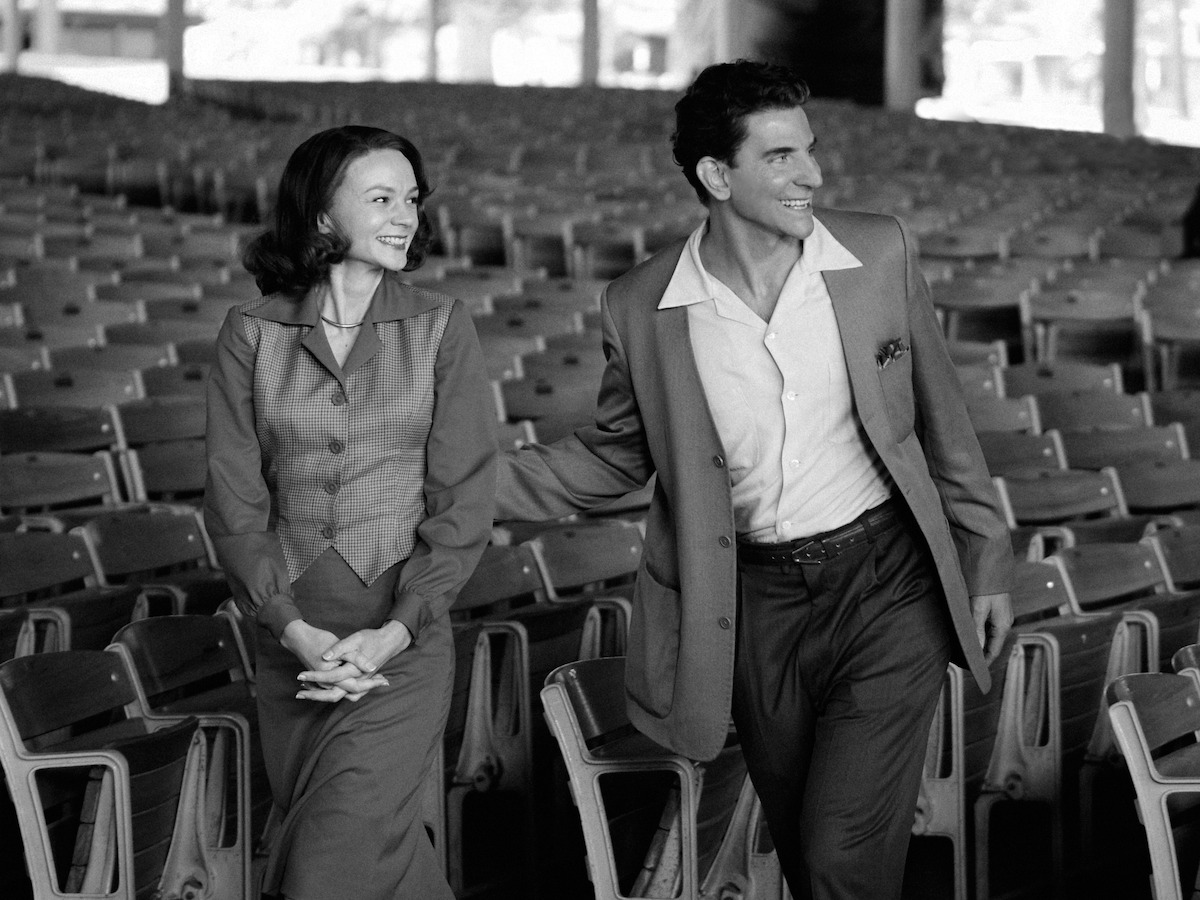

Photo by Jason McDonald/Netflix

★★☆☆☆ (2 stars)

Oscar-bait is not a term that I often fling around — especially not since it’s become the “industry plant” buzzword of the film industry — but Bradley Cooper’s “Maestro” was nothing if not a textbook example of Oscar-bait.

While I am sure it is true for most filmmakers that award recognition — especially from the prestige of the Oscars — is the dream scenario, when movies are made with only that in mind, they lose all their heart. It feels like audiences are more privy to a business transaction than a work of art.

“Maestro,” written, directed and produced by Bradley Cooper, calls itself an intimate look at the complicated relationship between famous composer Lenord Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) and his wife Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan). Focusing on their struggle to navigate his queerness and the separation between his world-renowned persona and the person he was in private. What it really is, is a surface-level story whose aim appears to be showcasing all of Cooper’s best moves.

Unfortunately, Cooper lost his grip on the movie in trying to prove his talent. Several aspects of the film work so well individually, but none of them come together cohesively.

The artistic, classical Hollywood choices Cooper made — shooting on 35mm film with changing aspect ratios and an alternation from black and white to color — did make it feel as if the movie could have come from an earlier time. In that sense, Cooper did a fantastic job with the overall tone of the movie, but this was not enough to make up for all its faults.

Honoring his theater background, there are a few musical-esque sequences in which the staging is on par with a choreographed dance; it was a unique but fitting way to guide the story. It would have been more impactful if this was a choice that followed through the film’s entirety, but they were just occasionally thrown in, disrupting the regular rhythm.

It felt like Cooper thought if he could distract his audience with pretty visuals then it would be enough to take attention away from the poor structure of the story. He failed to realize that audiences are too smart to fall into this trap.

If you enter this film with no prior knowledge of Lenord Bernstein, you will exit the film in just about the same way you entered. There is no clear introduction to who Bernstein is or how culturally significant his accomplishments were. While it should not be a director’s job to walk their audience through an exact play-by-play of who is who and what means what, the story should provide enough information for us to fill in the blanks on our own. This one did not.

The film picks up right as a young, 25-year-old Bernstein is brought on last minute to make his debut conducting the Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall in 1943, at that point on you are assumed to know what his career entailed. The idea of a classical musician being a glamorous star and household name is one unfamiliar to the public and could have used some more exploration.

Cooper seemed to very narrowly pick and choose which parts of Bernstein’s life he wanted to portray. Many biopics that have come before have proven it possible to depict an entire life in just around 120 minutes, but “Maestro” does not. Everything felt incredibly underdeveloped, something unfortunately even the movie’s main focus — the marriage between Bernstein and Montealgre — cannot escape.

Their relationship is brought about so quickly that audiences are unable to get a good read on their dynamics before the marital troubles take center stage. The pacing was too fast for any emotional connection towards characters to build; if we can not attach feelings to the main characters, what kind of a story do you have?

That is not to say the film was completely heartless; Montealgre’s struggle to accept her husband’s extramarital activities as well as Bernstein’s guilt of needing more than what his wife can give him is handled with care, but these storylines go fairly neglected. While it is clear that these two loved each other through it all, the complexities of what that kind of love looks like were not highlighted enough.

This story has been a great passion project of Cooper’s, working for over six years to get the movie made — admiring the work of Bernstein and wanting to bring forth the life that was hidden from the public. So, it was strange to find that Cooper chose to paint Bernstein’s sexuality with distaste.

There is certainly a way to condemn cheating without turning Bernstein’s difficult, and often guilty, exploration of his queerness into the film’s villain. Instead, Cooper opted to go as far as to imply that his exploration was a completely selfish act. The movie completely disregards the intimidation that being subjected to homophobia puts on a person, let alone one in the limelight.

It is a shame that the acting talents of Mulligan were wasted on a script that gave her little to work with. Just as disappointing is that actor Bradley Cooper has to work with screenwriter Bradley Cooper. However, I can not even bring myself to claim that they did the best they could with what they were given. With unexplained accents that weave in and out of conversations and an age progression that is nearly impossible to track until the overbearing prosthetics come into play, they felt disconnected from their characters.

In an unexpected role, Sarah Silverman’s performance as Lenord’s sister Shirley Bernstein was the most consistently grounded. Though she did not appear in many scenes, she quietly took charge of those she did. Maya Hawke, though incredibly talented, does not seem to fit into any period other than the 21st century, and in a timeline that is already not super clear, her performance pulled me out of the story.

It will be a disappointment if the film succeeds in winning several Oscars. Rewarding such shallow work will only encourage the award-seeking filmmakers to proceed with all the wrong intentions.

Many senior directors, like Steven Speilberg, Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee have praised Cooper’s entrance into directing; I fear what the future of filmmaking looks like if he is considered one of our greatest promises.

Overall the film was an easily forgettable one, I do not see this movie leaving any kind of legacy, a shame considering the legacy Bernstein’s work has upheld.