When Tesla Lelone toured Seattle Pacific University, she watched as her classmates found community in campus clubs — Black Student Union, ‘Ohana ‘O Hawai’i, Filipino American Student Association, Haven — but found no organization reflecting her own Indigenous identity.

“They were like, ‘Go find your people,’” Lelone said. “I was the kid in the corner like, oh, there’s no one here.”

Lelone, now in her second quarter at SPU, helped fight the lack of representation she felt, becoming Cultural Chair of the newly-created Indigenous Peoples Club.

“I’m hoping that this club will kick start more representation, because it’s good to have your community on campus,” said President and founder Breanna Smith.

Smith, of Arizona’s Hopi Tribe, did not grow up in her Indigenous land or culture, and hopes to further her “journey of connection” through the IPC.

“I’m from Washington, I grew up way far away from my cultural identity,” Smith said. “I knew that if I created this club, a lot of other people would also be on a reconnection journey.”

The first meeting encouraged Indigenous students on campus to meet together in the community for the first time.

“There’s such a small percentage on campus, we would all really love to just have a community. Our first event, we had people come up like, ‘We’re so happy, we’ve never had one,’” Lelone said. “I really came to serve my community here, and to have community and culture together.”

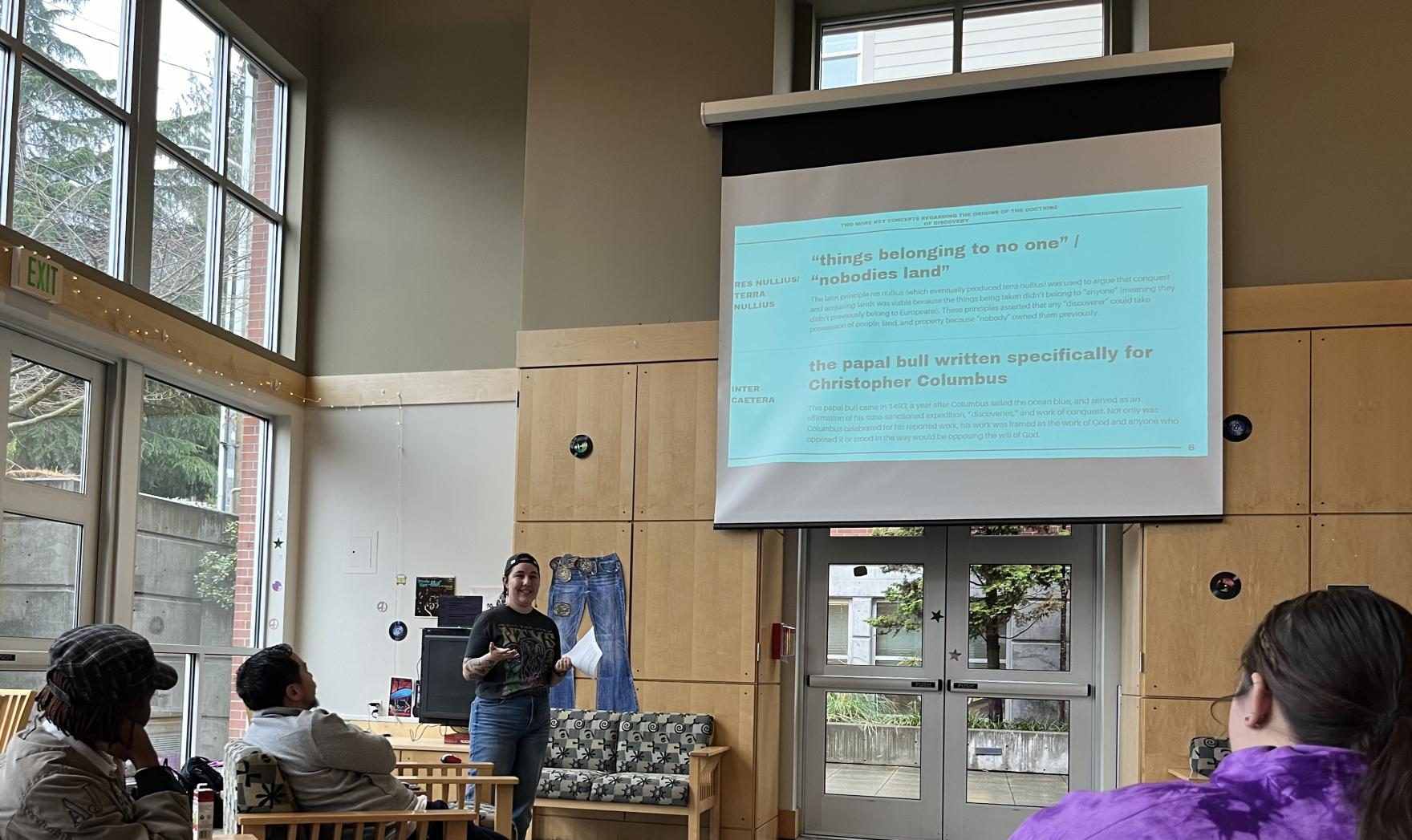

The Indigenous Peoples Club joined John Perkins Center Learn & Serve on Jan. 31 to learn about the Doctrine of Discovery, a philosophical and legal framework dating back to the 1400s, giving European Christian governments the moral and legal rights to invade and claim uninhabited land — that is, land inhabited by non-white, non-Christian peoples.

Delivered by graduate student Bizzy Feekes, the presentation explained the doctrine’s foundation is one of white supremacy and colonialism, not discovery.

“For Indigenous people, the root cause of so many of our issues in the world today is the Doctrine of Discovery,” Feekes said. “It was utilized as a blanket statement — if they’re not Christian, they’re not real people.”

Feekes listed specific consequences that reach into the modern Native experience. They have higher rates of incarceration, higher rates of suicide; they are least likely to graduate high school, and most likely to live in poverty. Overrepresented in the foster care system and maternal and infant mortality, Native Americans feel the devastating doctrine, destroying lives still.

The various tribes of 18 million people were decimated to less than 250,000 due to various explorers’ “discovery” of the United States and destroyal of those already there — a loss of history, culture, language and life felt deeply by every generation since.

The Doctrine of Discovery gave the foundation for the enslavement, exploitation, extraction, extermination and extinction of Native peoples, as presented by Feekes.

“Making this presentation was much harder than I had anticipated,” Feekes said. “It’s a topic I’m deeply passionate about and very tied to.”

Feekes, in SPU’s seminary, is set to graduate this year with a Master’s in Art in theology with a concentration in reconciliation and intercultural studies. Being familiar with this topic in academic spheres, they presented the information and implications with accessible language and lived experiences.

“I was trying to make it digestible – not to dumb it down, because I never approach an audience and think they’re dumb, but trying to make the language accessible is a huge key for me,” Feekes said. “When we talk about things like the doctrine of discovery, we have to get everyone to see it.”

Feekes, artist-in-residence at the Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery, shared quotes from executive director and co-founder Sarah Augustine.

“[The Coalition] is this organization doing the daunting work of Indigenous justice,” Feekes said. “So much of what I’ve learned about the Doctrine of Discovery has come from my experience with them.”

Feekes relies on those who have “already walked this path before,” and finds deep connection in learning and growing as communities. Such a community is key for Indigenous students in a college environment.

“I’m really leaning into this core Indigenous value, that we’re joining work that’s already started,” Feekes said.

A community for Indigenous students is vital, especially in the higher education sphere. Lelone, of Washington’s Colville Confederated Tribes, found community and belonging in the IPC.

“I’m glad we have the club now,” Lelone said. “It’s been so long without any representation, that we all have so many ideas and all just work well together.”

Smith, Lelone and other club officers are bursting with ideas to combine cultural education with fun activities. Club events in the future could feature cultural food, beading activities and Words of the Day from the Salish and Makah languages.

“It’s open to everyone to come,” Smith said. “You don’t have to be Indigenous to be a part of it, we want to educate.”

Feekes used the language of her tribe, Wisconsin’s Ho-Chunk, to conclude the presentation: Pinagigi. Žēgųkīra (Thank you. That is all.)The IPC will be selling fry bread, huckleberry cake, and Douglas fir tea at SPU’s Hello Festival on Thursday, Feb. 15 in Tiffany Loop from 5 to 7 p.m.