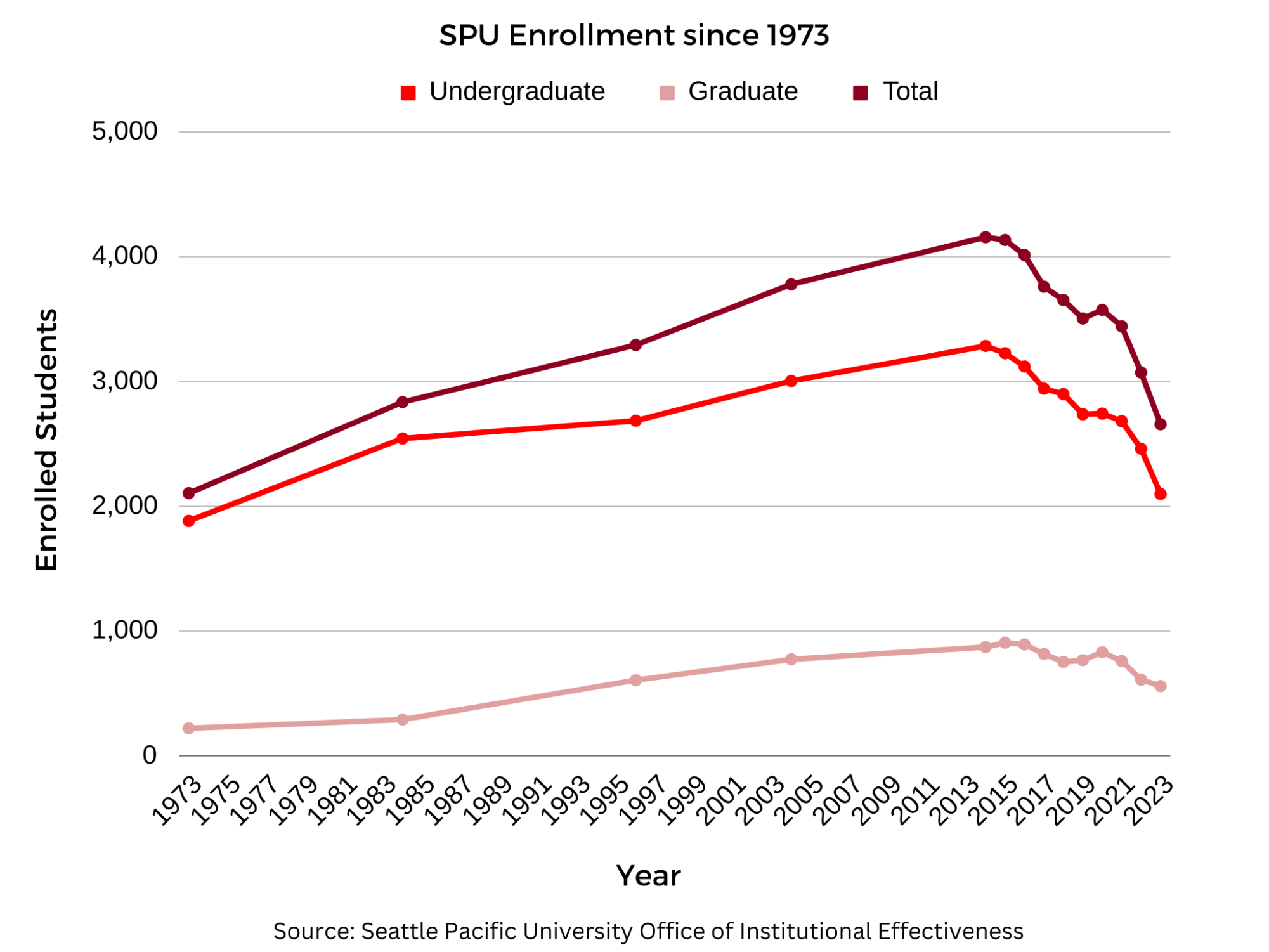

In the ‘70s, just over two thousand students wandered Tiffany Loop, studied in Ames Library and pursued degrees at Seattle Pacific University. Enrollment steadily increased for the next four decades to its peak — 4,157 undergraduate and graduate students in 2014.

Over the next ten years, enrollment dropped by more than a thousand students, hitting 2,658 in 2023. Universities across the U.S. are nervous about enrollment for a variety of reasons, with the primary cause being simple: there are just fewer college-age people around.

According to the Pew Research Center, fertility in the United States hit a decline in 2008. Birthrates never recovered from this nosedive, and, according to CUPA-HR, regional bachelor’s institutions like SPU can expect heavy losses in enrollment by 2029.

Of the students around, fewer are choosing college as their after-high school path. This tendency could be attributed to increasing career and life opportunities outside of college or the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education.

For Seattle University student Vegher Vegher, skyrocketing tuition rates are on the list.

“People don’t want to go to college because they can’t pay. Everything is becoming too expensive, and jobs aren’t paying enough for people to be able to go and do the things that they want to do,” Vegher said. “I also think people are now realizing that if you want to do something, you don’t have to necessarily get a degree to do that.”

As the student population shrinks, the student market grows more intense for traditional universities. Online programs, four-year community college degrees, and various institutions all vie for students’ acceptance, the way students used to vie for theirs.

“When a student’s admitted to SPU, we’re competing with at least four or five other schools. It didn’t used to be that way,” said Bryan Jones, associate vice president for admissions. “Schools are more and more sophisticated, so we’ve had more and more competition.”

SPU — already teetering on the demographic cliff and rebuilding from COVID-19’s enrollment losses — faced earlier hits to enrollment when they appeared in the news due to on-campus protests around their LGBTQ-excluding hiring policy.

“From an overall perspective, regardless of whatever those issues are, not a good thing,” Jones said. “We don’t want to be in the news for anything other than all these positive things we’re doing and what a wonderful place this is to go to school.”

Jayce Goodpaster, a junior political science and politics, philosophy and economics major, feels that SPU’s reputation is unsteady.

“Historically, SPU was a good place to go because people were like, ‘Oh, it’s a conservative Christian school which provides job opportunities because the kids are trustworthy.’ My grandma, that’s how she thinks,” Goodpaster said.

It is hard to measure how the controversy and news coverage impacted SPU enrollment, but Goodpaster feels the impact will last.

“What’s the reputation we had?” Goodpaster said. “I think that we’ve just lost that as time has gone on.”

In the face of declining enrollment and other factors, SPU announced intensive budget, program and faculty cuts. This downsizing of SPU is both a result and cause of student decreasement.

“I think that as SPU continues to make cuts, we’re going to see a lot less people apply here, simply because there’s going to be less offered,” Goodpaster said. “We would get those students, and now we don’t anymore because we don’t have those programs.”

Senior systems and data manager Tim Gatlin is responsible for all the official numbers reporting and predictive models with the Office of Institutional Effectiveness team, shrunk by SPU’s cuts, and aims to be objective in the analytics he provides.

“We’re trying to be more realistic from now on,” Gatlin said. “When we aren’t, they set up the budgets based on an optimistic view and we come in short. We then have to deal with those circumstances.”

For Jones and the admissions team, getting numbers back up includes focusing on desired demographics, specifically out-of-state and Christian students.

“We’ve definitely seen a decline in the number of Christian students choosing SPU and it’s a bit problematic,” Jones said. “Being a Christian university, we obviously would like to regain those numbers that we used to have more of.”

The all-new admissions team is focusing on the Christian identity of SPU in marketing. They hope to achieve enrollment through a presence at Christian college fairs, targeted advertising and out-of-state travel.

“What does it mean to be a Christian university today? How can we deliver that?” Jones said. “We’ve been able to hire a fantastic new team that has fresh ideas, fresh energy, enthusiasm for SPU, for our Christian mission identity, and where we’re trying to go.”

Going forward, Jones predicts SPU’s Free Methodist identity will “certainly be something we are known for.”

“Who knows what the size will be, who knows what are the right sizes, right?” Jones said.

The recent application deadline of Jan. 15 was extended by one month. The number of applications received is just below last year’s. If enrollment follows its current trend, there will be a 3% reduction of students in 2024 — 2500 in total, nearing the number of students SPU had in the ‘70s.

In the future, students will wander Tiffany Loop, study in Ames Library and pursue degrees at Seattle Pacific University — there might just be less of them.