★★★☆☆ – 3.0 stars

Nicolas Cage has one of the most eccentric careers of a critically-acclaimed actor. As a response to younger generations becoming more familiar with Cage as the face of many viral memes, rather than for his prestigious Oscar-winning work, Cage’s roles have grown increasingly meta. With a filmography full of off-beat characters paired with his recent shift towards more self-aware media, it was only a matter of time before Cage found himself as the starring lead in a “Being John Malkovich”-Charlie Kaufman-esque nightmare come to life.

“Dream Scenario,” written and directed by Kristoffer Borgli, a Norwegian filmmaker made popular by his work focusing on the effects of the internet on the collective unconscious and self-image, finds himself garnering a lot of attention with the debut of his first English film. His work often thematically builds up the layers upon layers of new media overconsumption. While his films are more “out there” in concept, they are also very straightforward in their messaging; he is an artist with a clear purpose.

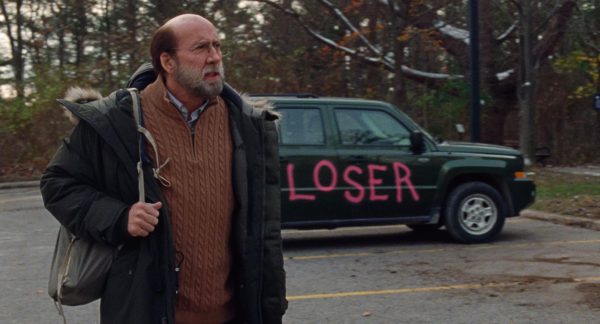

“Dream Scenario” follows evolutionary biology professor Paul Matthews, who becomes an overnight phenomenon when he suddenly begins to appear in millions of stranger’s dreams. Much like Cage himself, Paul quickly finds himself no longer able to control his narrative, so he opts to play the role given to him.

Borgli introduces us to Paul via a lecture given to his near-empty classroom. In this lecture, he suggests that zebra stripes act not as a way to blend in with nature, but to disappear in a crowd, something you could guess Paul would know a lot about just by looking at him.

Paul is your stereotypical “normal” guy, or at least he tries to be. Paul is the kind of guy to rehearse social interactions and laugh at his own terrible jokes, literally. On the outside, he seems content with his quiet life, but like most, Paul clings to a deep inner desire for recognition.

Eventually, the dreams, and his life, unravel into nightmares, leaving Paul, who became a sensation for virtually doing nothing, to navigate a world in which he has become a social pariah for again, doing nothing.

The movie draws a thin line between dreams and reality, putting us in the mindset of both the dreamer and Paul. While Paul cannot wrap his brain around the reality he is living, neither can the audience, which leaves viewers all the more confused as they find themselves beginning to also fear the presence of Nicolas Cage’s unnerving, yet innocent smile.

Benjamin Loeb’s cinematography brilliantly plays with angles, lighting, camera lenses and cuts to disorient viewers and keep them second-guessing what is reality and what exists solely in the dream space. This works to further play into the idea that dreams can alter people’s waking thoughts.

What is so striking and truly terrifying about this movie is that none of it seems at all unrealistic. Though the premise might be a bit far-fetched, after acknowledging the nature of society’s unhealthy trend cycles, one can begin to see that everything in the movie has happened before and will happen again, just under different, less extreme circumstances.

The tone of the movie relies on this sense of realism; with many awkward moments that work to break audience tension while simultaneously using the uncomfortable interactions to strain the audience’s relationship with Paul. By not restricting itself to one genre, the movie accurately portrays the complexities of life.

Borgli explores our cycling relationship with media, the disturbing truth behind parasocial relationships, and our newfound obsession with turning nothing into something on a worldwide scale. In a time where media consumers and creators are always searching for a new phenomenon to fixate on, trends often find their form in the most mundane of things. What makes something interesting is people’s obsession with it.

Outside of Cage’s outstanding job at appearing to be anything but, there are not many memorable performances. No performance was strikingly bad, but none could have stood on their own — with maybe the exception of Julianne Nicholson, playing Paul’s wife, Janet. But it is hard to say if her performance sticks out more than others because it deserves to or because an enamored Paul is always leading us back to her.

The movie loses its momentum in the final act when the film decides the message is too smart for audiences. In explaining itself, the movie loses all of its soul in the process. For a movie that had great commentary on media literacy, or lack thereof, this was a huge disappointment. What was a stunning dark comedy with sci-fi elements becomes reminiscent of the commercialized afterschool fable meant to warn children off the internet.

Adapting into an overly explicit cautionary tale about the dangers of rapidly developing technology, cancel culture and the blending of online presence with real life, the film abandons its (far more interesting) initial tone. As a piece of art, the film would have been much better off leaving the audience to fill in the blanks themselves, more boldly proving Borglis’s point.

While the film was plenty enjoyable, it was too obviously attempting to walk the line between shocking American audiences without going too far into high-concept application and trying to be a deeply intellectual film. If the filmmakers had been bold enough to neglect the bounds of Hollywood expectations, the movie would have found itself gaining a lot more respect and likely pioneering the reintroduction of modern experimental foreign horror concepts to the more modest and sheltered American audience.

The movie leaves audiences with a lot to reexamine, whether that be a deep debate about media consumption or the question of whether you’ll ever really look at Nicolas Cage the same again.