Oct. 5 marked a momentous opening reception for an exhibition at The Fyre, a downtown Seattle arts museum.

Quenton Baker, a poet and Seattle native, was the star of his own exhibition, “Ballast.” Baker read a sample of poems depicting the slave revolt of 1841, one of the few successful slave revolts documented in U.S. history.

As soon as he stepped onto the stage, the audience was captivated by him.

Laughter rumbled at all the right times during Quenton Baker’s opening speech to his audience, who gathered to experience his venture into public poetry. All ears were poised to pick what wisdom and education they could from the words being spoken at the podium.

Politely, mildly, Baker asked the audience if it would be alright if he read some of his work. His poems, however, did not politely engage the audience. Instead, his words demanded the attention of the minds of listeners, both during the reading and long after the show was over.

With the gift of powerful tone and a firm voice, he articulated the thoughts and feelings which he imagined circulated the minds of revolting slaves in the middle of the 19th century. The manifestation created a melancholic, brutally-realistic description of the time after slavery for these historical figures.

Baker said the poems he read were from an “ongoing manuscript.” The work used in the exhibition focused on slave revolt. He did not reveal anything more about the manuscript the poems were a part of, but he did give insight as to where, emotionally, the existing poems came from.

“[The poems] were inspired by, I think, probably the same thing that all of my work is inspired by, which is the desire to bear witness,” Baker said.

Stepping into the exhibit after the show made one thing apparent: Baker aimed to vividly recreate this event from history.

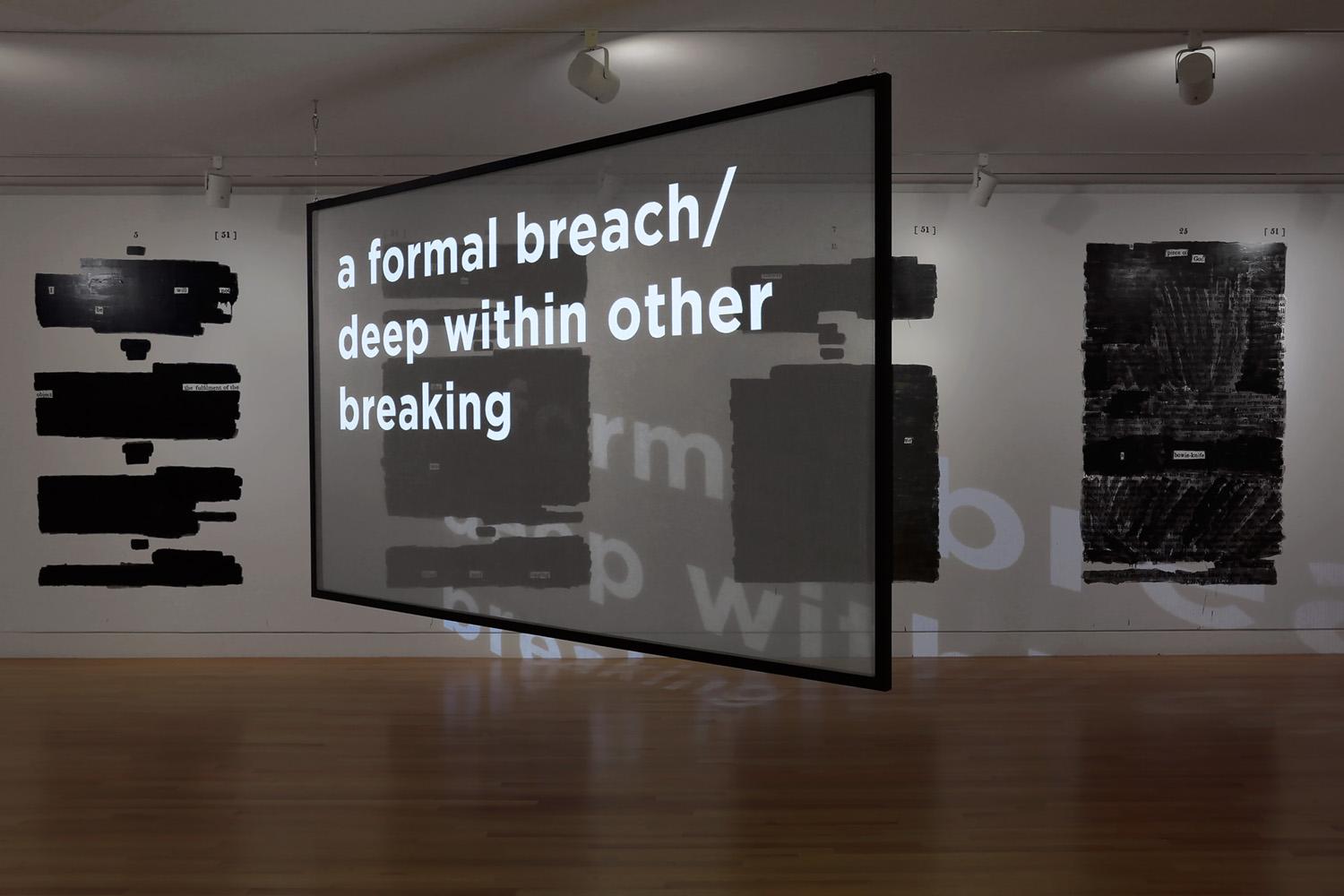

Along the walls of the exhibition were intentionally-blackened Senate documents that highlighted the case of the slave revolt, using the form of erasure art, a type of art that involves taking an existing document and covering part or all of it to create a different meaning. These erasures revealed unseen messages in the text to create a wholly different experience from its base form.

In the center of the room were two projection screens, which displayed Baker’s poetry as ever-changing sentences that quickly faded, only to be replaced by the next set of readings.

In fact, he is not a fan of erasure poems either, despite the erasure poems displayed in his exhibition. He recalled being “timid” at first with the idea of using erasure for “Ballast,” but he eventually was able to use it with purpose and intention in this particular work.

“That’s part of what this entire project is about,” Baker said. “It’s also about being able to create and exist under constraint, and it’s about being able to lend shape to one another, to be in community with one another, across time and across space.”

Baker has an MFA in poetry from the University of Southern Maine and in 2016, he published his debut book through Willow Books, titled “This Glittering Republic.”

His influence on the crowd on Friday night demonstrated his capability to convey a forgotten subject. Many do not know the success of the slave revolt aboard the ship Creole, and Baker himself was surprised to find that he had not come across the case until now, according to an article in the Seattle Met by Stefan Milne.

Baker sees self-integrity as the most important part of any process.

“You never have any control over if your work gets published or if anyone’s interested in it, but what you do have control over is how hard you work on your craft,” Baker said.

“The advice that I always still give to myself is to make sure that I’m working as hard as I can on making the work that I want to make. That’s the most important thing.”

“Ballast” will be open at The Frye from Oct. 6, 2018 to Feb. 3, 2019. Another reading is scheduled for Thursday, Nov. 1 at 7 p.m. Admission is free.