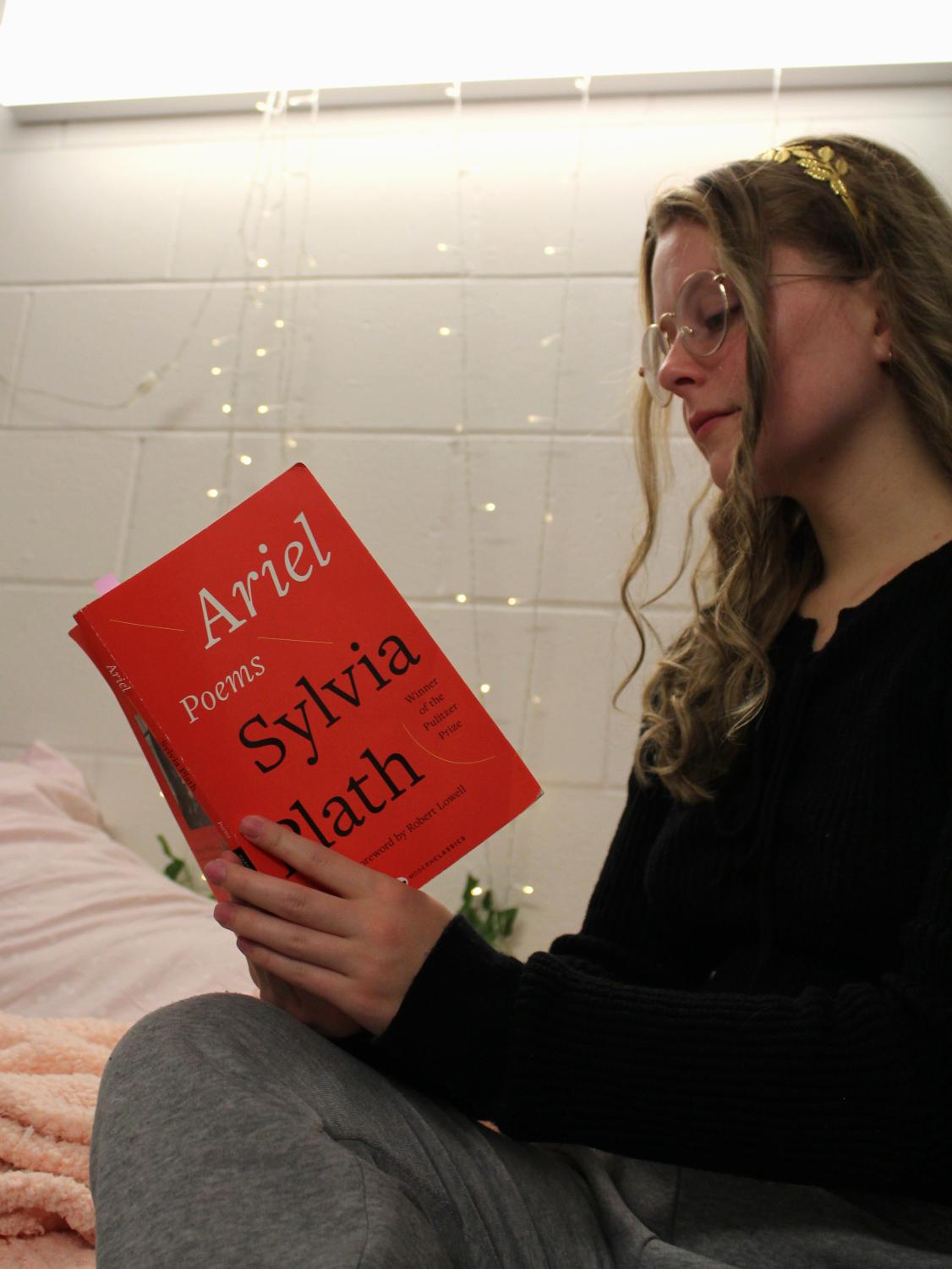

Until death do we part

Slyvia Plath’s “Ariel” promotes readers to find hope in their struggles despite unfortunate circumstances

October 14, 2022

For many people who come from the poetry community, Sylvia Plath’s works are beautiful, despite her emphasis on the difficult topic of suicide. A famous and successful artist, Plath could not take the idea of living anymore. In society, people often romanticize death and the what-ifs of not waking up to see another tomorrow.

In her final poetry book before her life ended in 1963, “Ariel,” Plath outlines the dark side of her life in a long series of poems that highlight her desire to leave the planet behind while also illustrating the small bits of light she was able to find during rough times.

Plath started her notable poetry career in 1941 when she was only eight, her poem titled “Poem” getting published in the Boston Herald. She wrote that poem less than a year before her authoritarian father, Otto Plath, passed. His strict nature inspired her poem “Daddy”, written in 1962, where she expresses the weight lifted off of her shoulders that she will never be able to see him again in the physical sense.

“Daddy” was written four months before her final suicide attempt and one month after separating from her toxic partner. She compares her father to a shoe that suffocates a foot with no room to breathe or speak. With a father of German roots, she felt as though he hated her as much as a person of Jewish heritage, which, as a person born in the prime of World War II, was very prevalent in her memory.

Since her father was dead by the time she was ten, she never got the chance to resolve the problems she had with him, meaning she was constantly trying to chase him down, not excluding the path of death, and not the man she married. Though she likely missed the resemblance in her husband when she said her vows, by the time of their separation, she knew her initial attraction was the longing to fill the hole her father had left in her life, which only tortured her more.

Her father mistreated her and took her for granted, but he wasn’t the last.

During her college years at Smith College, she met a charming man named Ted Hughes who was also a poet. It started as a passionate love story, both becoming each other’s muses, more for her than for him. It didn’t start abusive. But the happy honeymoon phase didn’t last long for the two of them, and after their marriage, she had to deal with domestic violence, wishes of death from herself and him and a miscarriage, not to mention the number of women he cheated on her with.

After her second child was born, she was dealing with the separation and her husband living with another woman. Plath felt as though her children, specifically her son, were the only constant in her life – the only one she could rely on. Thus came her poem “Nick and the Candlestick.”

While the nights get longer and her depression worsens, her son reminds her of the beginnings of this world, showing her there is beauty in pain. The pain is labor and the constant spiral of horrible thoughts and feelings she experiences every day after his birth. She claims that “the blood runs clean” implying that her son is innocent of the sins that captivate the world and that he is her last hope of the world being a healthy place to live. Within the poem, Sylvia Plath tells her son, Nicholas, that the pain she feels is not caused by him, and he should learn to be happy.

Throughout the series of poems in “Ariel”, it seems as though she’s crying out for help. In “Lady Lazarus,” she knows everyone who speaks of her sees her as the “troubled,” “sad” lady who lives alone with her two young children. She talks about the many attempts she took on her own life, stating, “The first time it happened I was ten. It was an accident. The second time I meant to last it out and not come back at all.” In those lines, her frustration and sadness are overwhelming.

Even if the attempt is hard to relate to, the hopelessness that can occur is all too familiar for some people. Many feel grateful for a new chance at life, while others feel the shame from confronting loved ones, and the grief of a “foiled” escape. For her, the attempts she made in her life only made her poems more dramatic and desperate, since her books and famous acquaintances had led her into the public’s eye.

While her widower husband was left to deal with the blame throughout the aftermath of her death and even his own, some sympathy can be felt for him. He shouldn’t be forgiven for her turmoil, but there’s only so much guilt someone endures until it becomes torture.

The fact that Ted Hughes arranged her poems into “Ariel” could make anyone’s blood boil. Still, it’s hard to pass up the opportunity to read a collection of her final poems – poems from right before she ended her life, poems longing for the beauty of life and dreading the heavy tomorrow, poems ultimately romanticizing a tragedy that must be treated with much care and respect.