A brief history of campus protest, for obvious reasons

June 2, 2022

As an alum I can testify that my education at Seattle Pacific University was lacking in a few areas.

My political science courses were sparing on queer civil rights in the United States, and I cannot recall any real discussion of activism on college campuses as a force for change. Perhaps I dozed off in class once or twice.

However, I’m proud to report that I’m now a bit more informed on these topics.

I hope that this article can serve as a resource to support the ongoing struggle for queer justice on campus. Hopefully soon I and my fellow alums can stop being embarrassed to include our alma mater on our resúmes.

This is not going to be a list of tools and techniques, like James Stout’s “How to Remove A Statue with Science” for Popular Mechanics (although many students across the country used these methods to further reconciliation on their campuses in 2020). Instead our story begins during one of the most turbulent times in U.S. history: the sixties.

In 1960, the Students for Democratic Society advocated for more progressive and inclusive policies in the Democratic Party. While they were once the party of the Confederacy, a century later, not all democrats held to the white supremacist beliefs of their predecessors. The SDS helped push leaders in the Democratic Party to become the party of progress.

With passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, more and more students of color were able to access higher education. Students formed Black Student Unions to advocate for the growing number of black students on predominantly white campuses. Modeled after organizations like the SDS, the first BSU was founded in 1966 at San Francisco State College.

Notably, BSU chapters at the University of Washington were able to secure their demands for racial reform using sit-ins and light vandalism. According to Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, without the work of Black Student Unions, the field of Black Studies would not exist in this country.

Around the same time, campus organizers around the country were rallying against the U.S. war in Vietnam. With the alternative being a death overseas, many in the anti-war movement felt destruction of property constituted reasonable protest. Students at Kent State University torched their school’s ROTC building.

Two days after the burning, on May 4, 1970, National Guard soldiers were ordered to clear a peaceful gathering of anti-war protestors. After firing tear gas and pursuing the dispersing crowd, the soldiers opened fire on unarmed students, killing four and wounding nine.

In solidarity with the Kent State Martyrs, students across the country walked-out from classes. At the UW, campus organizers (including the local SDS chapter) staged a student strike the very next day. Rallying six thousand students to march from the campus onto I-5, they blocked the freeway for hours. Traffic blockings and class walkouts continued until May 8, with similar demonstrations happening across the country.

While these marches did not bring an end to the war in Vietnam, it forced President Nixon to end the recent invasion of Cambodia. It also led to the War Powers Act of 1973 and the ratification of the 26th Amendment: limiting the president’s war-making authority and lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, respectively. The president’s chief of staff blames the protests surrounding the shootings with beginning Nixon’s insecure slide towards ordering the Watergate burglary. Before long and faced with impeachment, President Nixon would soon resign from office.

Students have always been on the front line of political change. Many of the Founding Fathers (not of all of whom owned slaves, mind you) were educated in Colonial Colleges. These schools were full of revolutionaries, despite being founded by the British Empire. All but two of these universities would change their names after independence.

Perhaps most strikingly, King’s College became Columbia University. After all, the U.S. was founded on the principle that no earthly king should rule over this land.

It is also important to remember that the first Pride was a riot, not a march. After repeated harassment from police outside of one of their only safe havens in Greenwich Village, NYC, the queer community rose up. As cops tried to make arrests, the community began chants of “We didn’t pay the bribe, someone paid them.”

When officers escalated the situation, the crowd began throwing coins (to pay off the bribe, of course). Since the cops wouldn’t stop hurting protestors, the community moved on to throwing beer cans they took from bars. Since the cops wouldn’t stop, next came bricks from a nearby construction site.

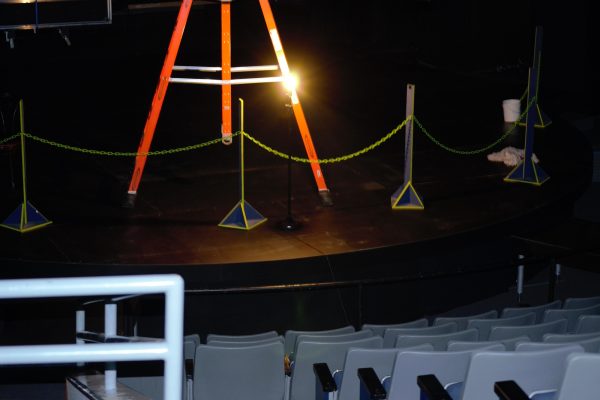

Seattle Pacific University has refused to stop discriminating against students and faculty based on homophobic principles. SPU students so far have tried protests and sit-ins. All I can say is SPU is lucky there is a coin shortage and that no beer cans are allowed on campus. If our school survives this crisis, I hope to see your story added to this history of student victory.

Michael Crowley • Jun 14, 2022 at 4:49 pm

I’m an SPU alum who attended in the late ’80’s, and was there when campus protests at SPU targeted the school’s investments in firms and businesses that supported the Apartheid regime in South Africa. I remember that student organizers built a cardboard shantytown on the lawn outside of Demaray Hall, and I remember spending an afternoon there studying.

I was not an organizer or a leader of those protests, and my part was relatively small, but I can tell you this: it got done. It took time, it took consistent effort and someone nearly running down one of my floormates when they got the bright idea to take their pickup truck through the shantytown, but the school eventually divested.

To everyone protesting SPU’s ongoing institutional homophobia, I tell you that story to tell you to keep going. You’ll win. You can do this.