Heritage and Halloween

Reconciling my pagan Christianity

October 28, 2021

Autumn represents a time of transformation and magic. My personal emphasis is on Halloween, or, as my Irish ancestors celebrated, Samhain (pronounced SOW-in). This period of death and harvest, of tangibility and spirituality, brought awareness and clarity over the years to the grappling between my current and ancestral identities.

My current identity is the heritage of being raised in Alabama. I belonged to a Southern family who attended a Southern church and adhered to Southern traditions of conservatism and skepticism. And these ideas heavily emerged around my favorite holiday, Halloween, was strictly forbidden to be celebrated, endorsed or favored. I asked my mother and church leaders why I couldn’t go trick-or-treating or carve a Jack-o-lantern. I was told Halloween is evil, the devil’s holiday, that demons and spirits and evil things should never be entertained in the life of a Christian.

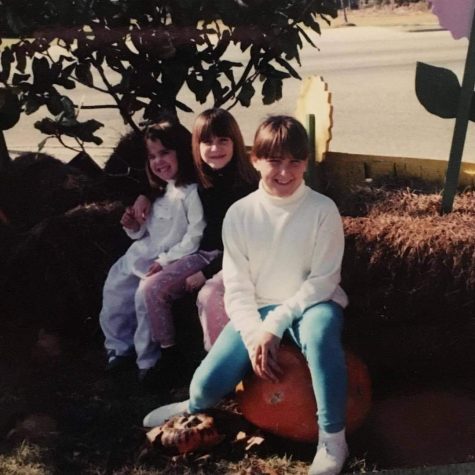

But my church did host a “Harvest Festival” on October 31st as an alternative to the devilish night of debaucherous candy hunting where children could come and collect candy from booths set up by the various ministries. Heavy rules were imposed on the children’s costumes: no blood, ghosts, witches or skeletons. Nothing that could be scary or ungodly.

Around 17, I learned that Christmas, Easter and Halloween were all pagan holidays that had been Christianized after missionaries assimilated the cultures that created these festivals. I sought answers from my church leaders about why the church erased these histories, these identities, and found none. I was not allowed curiosity about or engagement with these histories– my history.

I broke away from the Southern Christian mindset and in my rebelliousness against religious censorship, discovered Samhain. And I was surprised. Samhain was not the gruesome devilish night I had been taught to fear. It is a beautiful celebration of ancestors passed.

On Samhain, the veil between the dead and living becomes thin, allowing those who have passed on to cross over. Food offerings were made to ancestors, the powers that provided the harvest, and given to feed the poor. The carving of gourds and potatoes (pumpkins were used after Irish people immigrated to America) into lanterns and grisly faces doubly helped spirits find their families and ward off bad spirits. It was a culmination of family and community during a time of thankfulness, charity and remembrance.

I sought to connect with these Irish roots and embrace our traditions as best I could, thinking these were noble and good things to abide by and practice. My growing thought is that Samhain traditions are Christ-like, that the values of the holiday do not differ from those promoted by Jesus: Love thy neighbor, honor your family, tend to the poor.

But despite my love for this distant version of myself, there was intense pressure from my current identity to conform, to accept the church’s ruling, to become adopted into this family leaving all other versions of myself behind. This family had adopted my ancestors too, and erased the beauty of their culture, festivals and identity, giving them a new one.

Christianity claimed their old identity was sinful, ungodly, that they must abandon it in favor of the one being forced. Can I honor my ancestors through Samhain and say a prayer before taking a midterm? To accept one identity was to deny the other. So I thought.

A few years ago, I snuck out to a Halloween party dressed like the devil in a red dress, red horns, fake blood down my chin. As a handful of barely legal friends with few options on Halloween, we absconded to the Alabama woods and made a bonfire.

Beautiful people toppled and danced around the fire unsure what was a body or shadow or something else, the owls and laughter blended into a chant with the music from the cars, and the moon was high, cold, full. I was full, connected to the things within and beyond the firelight, to the people and the nature around me. And this is when I felt Irish. And I thanked God that I found a shred of myself under a Samhain moon.

As we move into this time of community, healing, generosity, and remembrance, I leave this traditional Samhain blessing to carry with you in the coming winter months.

Blessed be the ancestors, the ones whom life has fled.

Tonight we merry meet again, our own beloved dead.

The wheel of the year turns on, a new year in our sights.

The maiden has become the crone, we celebrate this night.

N • Nov 2, 2021 at 5:32 pm

This is beautifullly written. Thank you for writing this and sharing your journey.

Helen • Oct 28, 2021 at 12:24 pm

This made me so happy! I’m so glad I’m not alone in celebrating on campus! Blessed (early) Samhain! ❤️